“Fortune favors the bold.”

Virgil

“Show me a hero and I’ll write you a tragedy.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Note: this post covers what I think will be a complicated subject for general audiences. I did my best to make it understandable. Hopefully you can hang on until the end.

The Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy outlines a menu of practices that farmers and conservationists can use to reduce nutrient loss from farmed fields. One can sort them into multiple categories but one easy way of doing that is to divide them into what we in the biz call ‘in field’ and ‘edge of field’. In field practices usually require active decision making by the farmer; edge of field practices don’t.

Nitrogen (N), one of two macronutrients and arguably the major water pollutant generated by Cornbelt agriculture, can be intercepted from the agricultural drainage tile that underlies much of Iowa by edge of field (EOF) practices such as woodchip bioreactors, constructed wetlands, and saturated buffers. These all work in much the same way—nitrate (NO3-) is detained in an organic-rich environment where microorganisms ‘reduce’ NO3- to nitrous oxide (N2O—bad) and nitrogen gas (N2—good).

Nitrous oxide is a greenhouse gas with 300 times more warming potential than CO2 and results when water isn’t detained in the EOF practice long enough. When water is detained too long, the microorganisms consume all the NO3- and begin chemically reducing sulfate (SO42-), a process that also liberates mercury from the organic material making it ‘bioavailable’, resulting in a food chain populated with mad hatters posing as insects and fish. Eating fish that contain mercury is what we call sub-optimal. For these reasons, design and maintenance of EOF practices is critical to prevent the practice from becoming a source of pollution. This is a common theme in virtually all engineered pollution reduction strategies—mitigation of the pollution generates more pollution.

EOF practices do work to quench nitrate from field drainage tiles. It’s my (and many others’) firm belief that they are not a landscape scale solution; in other words, they’re not something that can solve nutrient pollution at large spatial scales (subjective, but I’ll say more than 1000 square miles) because of cost of construction, finite lifetimes (the organic material in woodchip bioreactors can become exhausted in 10 years or less) and limitations related to siting. We need 10s of thousands of these things in Iowa to make a serious dent in nitrate pollution. We have about 100 constructed wetlands and a few dozen of the other practices. I’ve heard people say there aren’t enough trees in Iowa to build all the woodchip bioreactors we need and we would require logged trees from northern Minnesota to make this practical.

I’ve long had a visceral negative reaction to providing public money for EOF stuff because it requires the farmer to change nothing about his/her operation, which, conversely, is why some in the conservation world love them. How do we give farmers license to do WHATEVER THEY WANT with inputs (i.e. commercial fertilizer and manure) and then ask the taxpayer to pay to mitigate the pollution at the field’s edge? It’s perverse policy. It’s like encouraging graffitists to practice their craft while spending taxpayer money to sandblast their handiwork. How does this make sense?

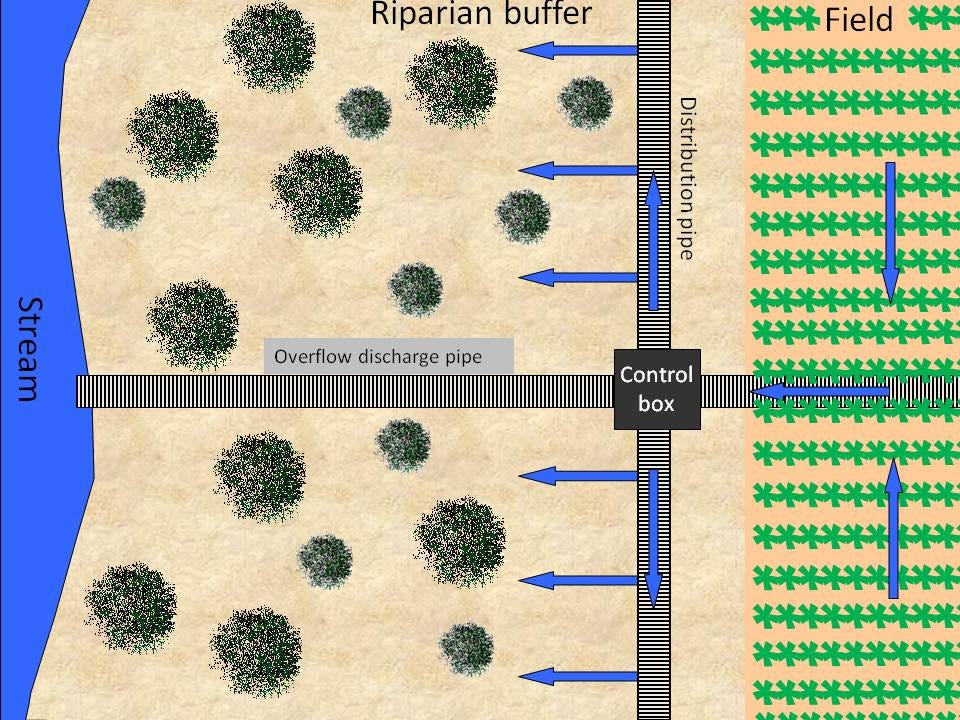

The latest rage in EOF is the saturated buffer. These cost a tiny fraction of a constructed wetland and about a third to half of a woodchip bioreactor, and don’t require the land necessary for a wetland or the woodchips of a bioreactor. Instead of discharging directly to a stream, water from a field tile is intercepted by an underground header running parallel to the adjacent stream. Water is dispersed along the length of the header and trickles out through the roots and organic material in the riparian area along the stream, which consume the nitrate before it enters the stream. Near as I can tell, the idea has been around for about 25 years but became important in Iowa with research conducted by Tom Isenhart (ISU), Dan Jaynes (USDA) and several others (1-3).

The reason for the rage is because saturated buffers have been the featured practice in what is being billed as Batch and Build. Simply stated, this is construction of many similar practices within a small geographical area in a short time window. Presumably this lowers costs related to private contractors and their heavy equipment—efficiency. John Norwood, Polk County Soil and Water Commissioner and former Democratic candidate for Iowa Secretary of Agriculture, billed his brain as the birthplace of Batch and Build during his losing campaign, and the Des Moines Register featured the concept as Norwood spearheaded implementation of several practices in northern Polk County. Part of Norwood’s campaign pitch was basically this: if you’re going to do the nutrient strategy, this is how you do it. There are some players out there on the political playing field that thought Norwood did indeed deliver a clean hit to then- and current-Secretary of Ag Mike Naig on this. But Naig, who comes up with original ideas about as often as some other guy I’m tempted to mention, played Tony Soprano to Norwood’s Christopher Moltisanti after the latter fences a truck heist—Mike plucked Batch and Build from John’s hands quicker than Tony grabbed a roll of C-notes from Christopher’s.

Not to be outdone by their cohorts in Central Iowa, the Eastern Iowa conservation world (private contractors, public sector employees, NGOs etc.) thought that Batch and Build should get equal billing over here in Hawkeye country, and this is where things get interesting.

Cedar Rapids has long held the title of “City Least Troubled by Ag Pollution” and they’re proud of their ability to tolerate it. Presumably this keeps the guys smoking fat cigars in the board rooms of ADM and Cargill happy (1000 combined employees in Cedar Rapids). The city has had issues with drinking water nitrate in the past, but Iowa DNR recently declared the Cedar River, which keeps the city’s shallow wells filled with water, no longer impaired for nitrate. This ‘delisting’ of the river occurred a mere nine months after it contained nitrate concentrations 1.5 times greater than the safe drinking water limit. But the city is apparently run by Alfred E. Neuman fans and continues to tout its willingness to help the luckless and downtrodden farmers polluting the city’s water as they try to scratch out a living on the world’s best corn ground before they leave for Ft. Myers every winter.

Farmers agreeing to work with the batchers and builders get access to federal money that pays the entirety of the project cost—100% cost share. Not only that, but each farmer also gets paid a $1000 “inconvenience fee” just for allowing contractors access to the site so they can install the necessary infrastructure. If a farmer agrees to 10 practices on his property, he/she gets 10 inconvenience fees ($10k, in other words). Folks, I am not kidding you. I know, nice work if you can get it. Much or all of this money is now coming from Inflation Reduction Act and American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds. I don’t know about you, but thus far neither USDA nor Mike Naig has shown up on my doorstep with a $1000 check to compensate me for the inconvenience of my water being polluted.

I’ve followed this story for a long time now but hesitated to write about it because of its complexity and because I consciously don’t want to be labeled as ‘against everything’. People like me must be able and willing to call a strike when the ball crosses the plate. But then something happened about nine months ago, before I retired or even started considering retirement. A hero in the public sector came to me and said they couldn’t sleep at night because the game was rigged, and this person felt they needed to confide in someone. And then something else happened a month or so ago. A Soil and Water Commissioner came to me and said the same thing and a participating farmer was telling the commissioner the same thing. And a few other people were badgering me to write about this because it has been increasingly obvious that the whole thing has morphed into yet one more propaganda tool that big Ag and the conservation world can use to prop up their water quality cred. So here we are.

Conservation practices eligible for federal cost share must adhere to what is called a Practice Standard created by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), a branch of USDA. For something like a saturated buffer, this includes engineering design specifications that ensure the taxpayer doesn’t get ripped off. In the case of saturated buffers, the practice standard states that the buffer must capture “5% of the drainage system’s design flow, or whatever is practical.” I learned back in March that it didn’t always say that. It seems it used to say “5% of the drainage system’s design flow.” Period. I had heard rumors that certain people (I will leave them unnamed) associated with saturated buffer work had complained that the original practice standard was too onerous and severely limited the locations in Iowa where this practice could be installed. I can’t be certain but I assume the limitation relates to the length of the header pipe and the land required to accommodate the required length. If you needed 1000’ of stream-adjacent land to accommodate a pipe that will capture 5% of design flow and you’ve only got 500’, then no saturated buffer under the old practice standard. Under the new practice standard? No problemo. At the time (March), I and others scoured the internet looking for the original practice standard but couldn’t find it.

The hero sent it to me this week.

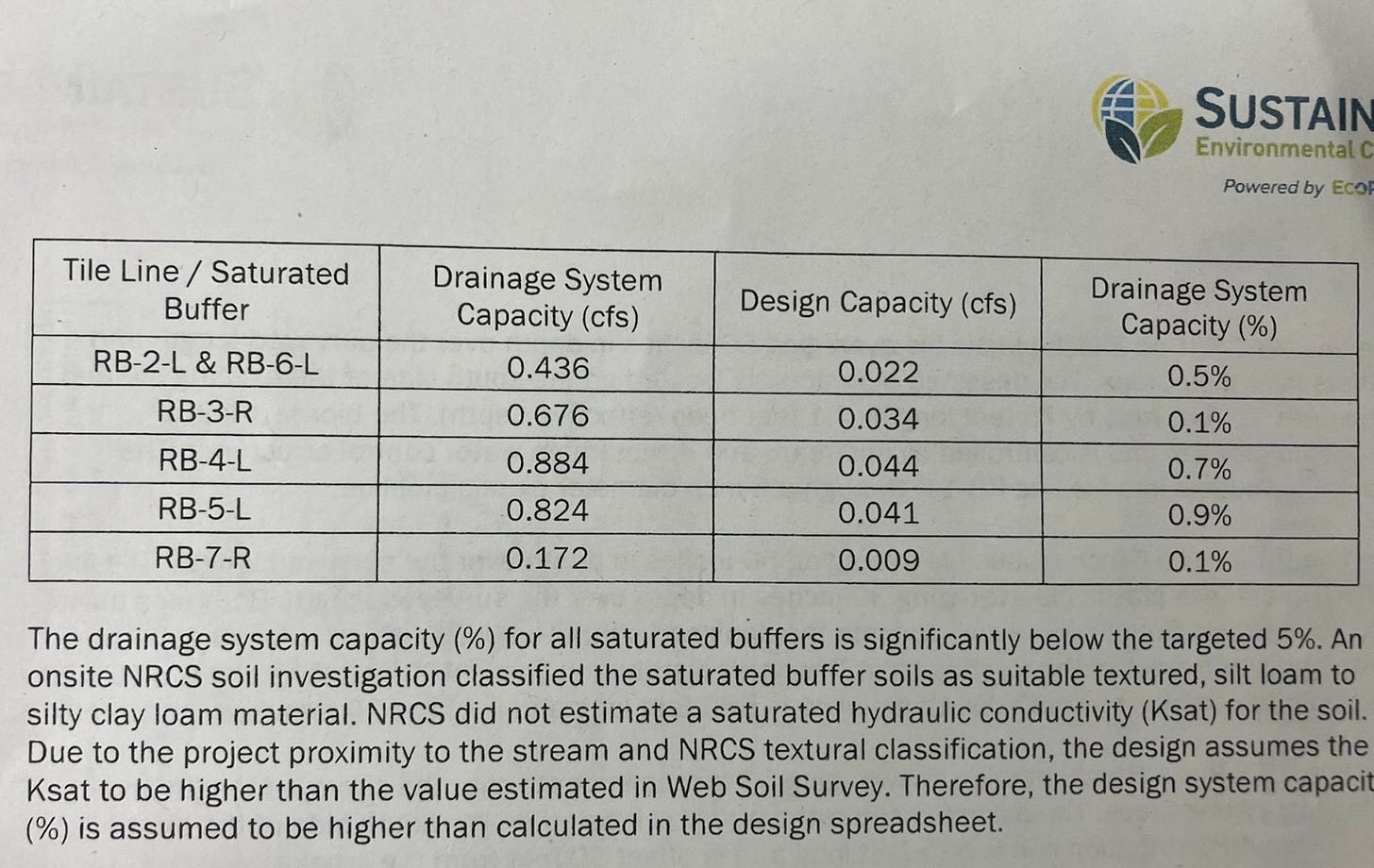

What exactly is the importance of this practice standard change? That’s illustrated by the conservation plans the aforementioned farmer provided to the Soil and Water Commissioner. The five saturated buffers shown in the table below capture 0.1 to 0.9% of the tile drainage system capacity. The conservation plan even states “The drainage system capacity (%) for all saturated buffers is significantly below the targeted 5%.”

Let’s look at the worst one there, the last one in the table. The drainage system capacity is 0.172 cubic feet per second (CFS). Although not strictly correct, you can think of this as ‘peak flow’, the maximum amount of water that can travel through that tile system. I know from my own work that for a field tile in Iowa, about 40% of the total tile water discharge will occur at flows less than 5% of peak flow. So, if the original practice standard of 5% minimum design was enforced, the saturated buffer could be expected to capture 40% of all the water over the course of a year. The rest (60%) is discharged directly to the stream and receives no treatment. But if it’s designed to treat 0.1% of peak flow, the total amount of water treated by the saturated buffer is far, far less. You might be inclined to say it’s capturing 1/50th of the water compared to the 5% design capacity. But since these relationships are non-linear, it’s probably even less than 1/50th.

A field tile in Iowa could be expected to be at peak flow for a few days up to a couple of weeks per year. In some dry years, it might never reach peak flow. But for the sake of argument, let’s say that tile is flowing at peak flow ALL THE TIME with nitrate at 20 mg/L (ppm) and that the saturated buffer quenches all of that nitrate. That means about 3 kg (6.6 pounds) of nitrogen per year (about $5 worth if you bought it as fertilizer) is being quenched by this particular saturated buffer that cost several thousand dollars to install and for which the farmer got a $1000 ‘inconvenience fee’. Now you can see why the hero couldn’t sleep at night. Oh, and statewide stream nitrate load averages 600 million pounds per year. To achieve the 45% Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy goal, you’d need about 2000 of the saturated buffer just described.

2000 per square mile across the entire state, that is.

Sure, you can assert that all the saturated buffers can’t be this bad—and they aren’t. But we have little idea what the benefit to the public is for any of them because we don’t have access to the conservation plans, which are not public information. I only have these because the farmer willingly provided them and because of my relationship with the Soil and Water Commissioner. But clearly these projects have value to people like Mike Naig and the ag advocacy organizations because, and let’s call this for what it is, they are props that can be used as the Big Ag and political establishments propagandize what they call ‘progress’ toward better water quality and Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy objectives. At worst, this is a money laundering operation that shovels dough into the pockets of farmers, earth movers and technical service providers with little or no benefit to the public, and revoltingly, under the guise of better water. If you want to make the case that it’s a jobs program, I could buy that theory pretty easily. People in the agencies, cities and NGOs like this stuff because it’s work and it enables them to demonstrate they’re doing ‘something.’ Some of them get fluffed by the ag groups for being good ‘partners’ and enabling the aggies to message this stuff for their own benefit. These “conservationists” rationalize it through the idea that this is the framework they’re left to work under, and they’re just trying to make the best of it. If the big guns in Des Moines (or West Des Moines) and D.C. say put diapers and bandaids on the landscape, then by god, that’s what they have to do, or find other work. It may be hard to argue with that, but from where I sit, that’s not much of a formula for a rewarding career, but who am I to judge.

Here's a final insult to injury. Google recently announced that they are contributing $150,000 to this Kabuki theatre. Google is a $280B company that spends $150,000 every 17 seconds. But now that I think about it, money laundering and green washing do seem to exist within the same weird word ecosystem.

If all this makes you mad or sad or both, just remember: there are heroes out there.

Jaynes, D.B. and Isenhart, T.M., 2019. Performance of saturated riparian buffers in Iowa, USA. Journal of Environmental Quality, 48(2), pp.289-296.

Jaynes, D.B. and Isenhart, T.M., 2014. Reconnecting tile drainage to riparian buffer hydrology for enhanced nitrate removal. Journal of environmental quality, 43(2), pp.631-638.

Groh, T.A., Davis, M.P., Isenhart, T.M., Jaynes, D.B. and Parkin, T.B., 2019. In situ denitrification in saturated riparian buffers. Journal of Environmental Quality, 48(2), pp.376-384.

About my book: The Swine Republic is a collection of essays about the intersection of Iowa politics, agriculture and environment, and the struggle for truth about Iowa’s water quality. Longer chapters that examine ‘how we got here’ and ‘the path forward’ bookend the essays. Foreword was beautifully written by Tom Philpott, author of Perilous Bounty.

On this leaky base under flyover skies the greens and not so greens brightly, yet so dimly, propose "sustainable" aviation fuels, to further lock in such inane land use ... until all the many ways this system is unsustainable are proven, not by reason but by failure. But not until after more costs and coercion (CO2 pipelines!) are suffered by those living under flyover skies. "For ours is an age of loss disguised as plenty" (Nathaniel Popkin)

You're right, Chris. My old brain couldn't wrap around the complicated first part but was able to comprehend the last part fine ... Thank goodness for brave ones, including yourself!! Mary