Nitrogen pollution in streams is characterized in two main ways—concentration and load. Concentration is the amount per unit volume, which for nitrate-nitrogen, is usually reported in milligrams per liter (mg/L) which is equivalent to parts per million (ppm). Concentration is important for the municipal drinking water supply industry because the maximum limit of nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N) allowed in water provided by public water supplies is 10 mg/L. Concentration is also the metric of concern if you’re a plant or animal living in a stream or lake and nitrate effects your life processes. Some things love it—algae and cyanobacteria, for example, while other things, like some fish species in their larval stages, not so much.

Load is the total mass (kg, tons, pounds, etc.) of the pollutant transported by a stream over a defined time period. It is calculated by multiplying the nitrate concentration by the amount of water in the river. Load indicates how much nitrate is being lost from our farming systems and many of our state and federal policies target this metric for improvement. For example, the objective of Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy is aligned with the Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Task Force, a consortium of several state agencies and tribes whose stated objective is a 45% reduction in both nitrogen and phosphorus loads to the Gulf by 2035 (pushed back because of lack of progress leading up to the original 2015 target date). Load is important in this context because Gulf volume is vast relative to that of the Mississippi River, which delivers most of the nutrients to the Gulf.

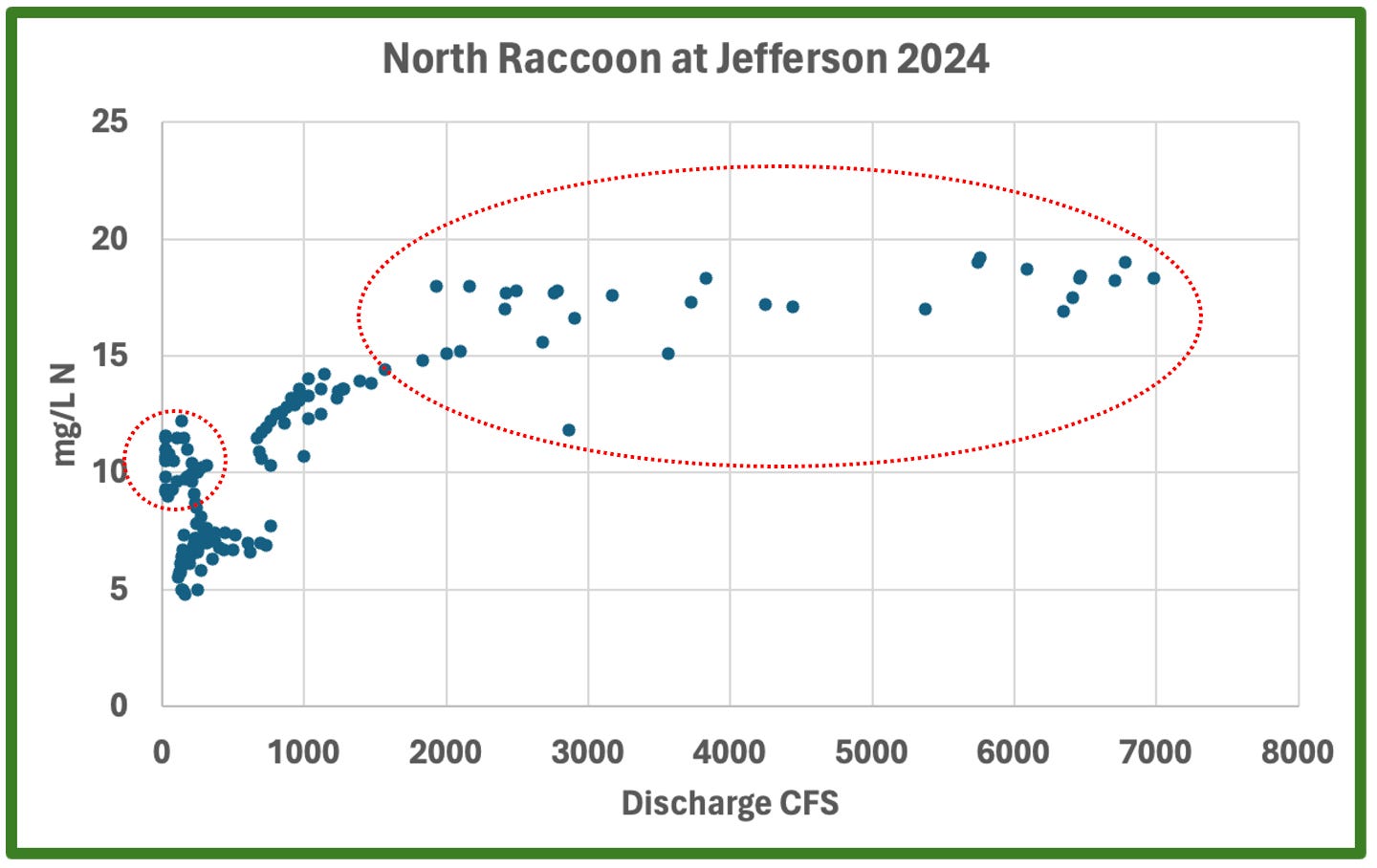

Over the long haul, load correlates more with river discharge than nitrate concentration. This means the amount of the pollutant getting to the stream is mostly dependent upon the amount of water traveling through the system. In some years, however, the concentration of nitrate does not correlate well with stream discharge, usually because the supply of the pollutant is so large that the water moving through the system is always encountering the pollutant on its way to the stream network. The graph below is a scatter plot of nitrogen concentration vs. river discharge in the North Raccoon River at Jefferson for 2024 (up to 5/24). Each dot is a day. You can see river nitrate increasing to 19 and staying there no matter what the discharge is, as long it’s above 1500 cubic feet per second (CFS) (red oval). You can also see that nitrate concentration has been pretty high at some very low flows (red circle to the left). That is atypical. These days on the left side of the graph happened earlier in the year for the most part, and this was a warning sign that a bomb was going to explode if the rains returned—every drop of water getting to the river had quite a bit of nitrate, meaning the supply of nitrate in the system was inordinately high.

I wrote a paper with others in 2017 that showed nitrate pollution in Iowa’s North Raccoon River was 57% transport (water) limited and 43% supply limited over the long haul. ‘Limited’ can be a confusing word in the this circumstance, and you might think of this instead as ‘controlled.’ Most years tend toward one or the other, and post drought years like 2024 tend to be supply controlled. After four years of drought, the supply of nitrogen on Iowa’s landscape might be as large as it’s ever been, largely because farmers refuse to modify their fertilizer inputs by basing them on the measurable amount of nitrogen in the soil. Any amount of rainfall making its way through the soil profile is going to encounter A LOT of supply—nitrate in the soil—and if that water can ultimately reach the stream, boom, stream nitrate is very high. High nitrate groundwater also contributes to this, as the water table rises to the level of field tiles discharging to streams after rain. Normal N loss resulting from normal rainfall didn’t happen over the previous few years because in dry conditions, a large percentage of the water gets used by crops or evaporates. Even so, farmers keep pouring on their usual amount without regard to what has happened in previous years.

There are many in agriculture that have a vague awareness that load relates strongly with river discharge. Their response to this has been to blame nitrate pollution on the weather. Early (pre-1910) monitoring data, however, shows that pre-settlement Iowa streams likely never exceeded 2 mg/L NO3-N; now streams can have 10-20 times that concentration and many never dip below 2 mg/L unless they are nearly completely dry.

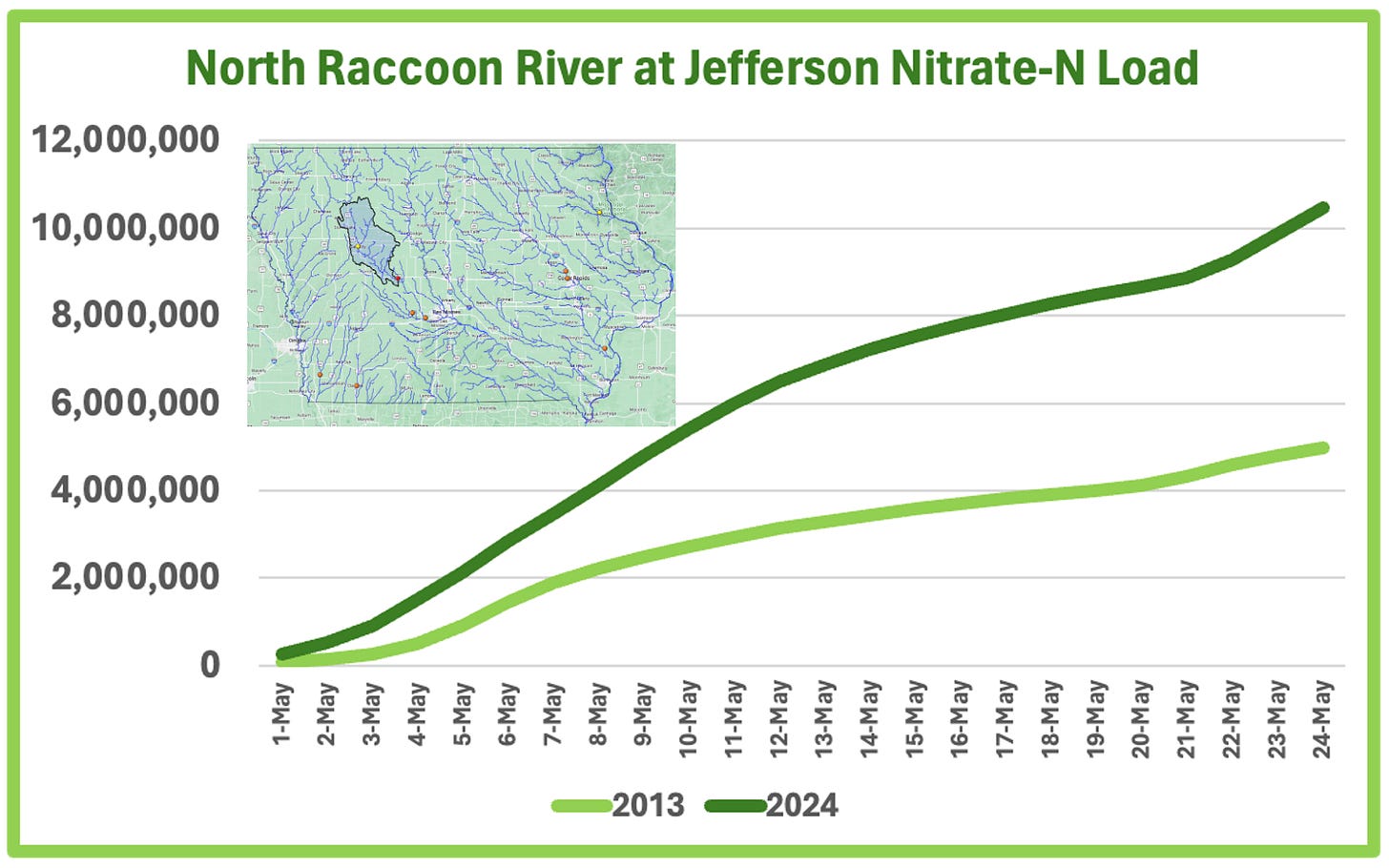

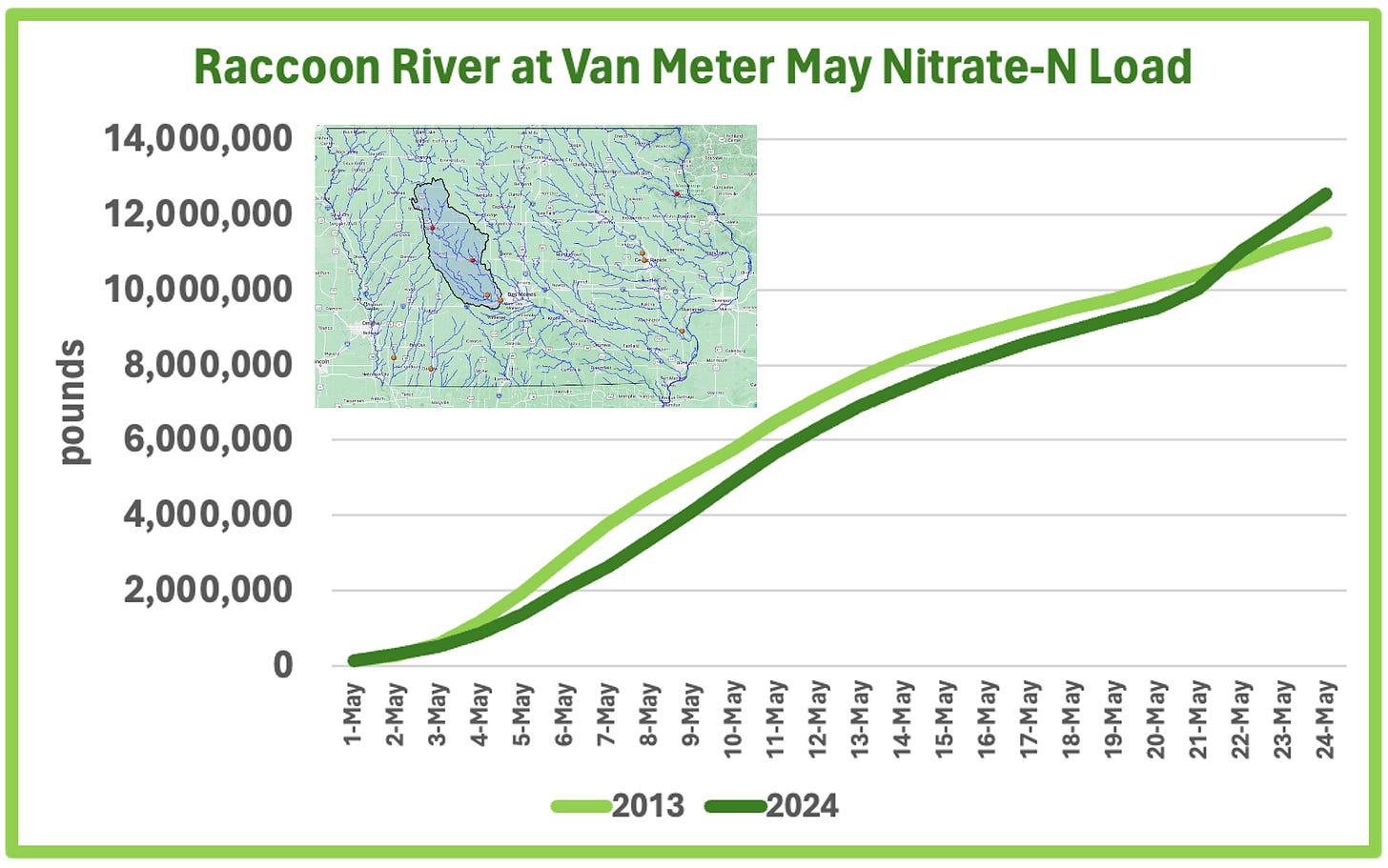

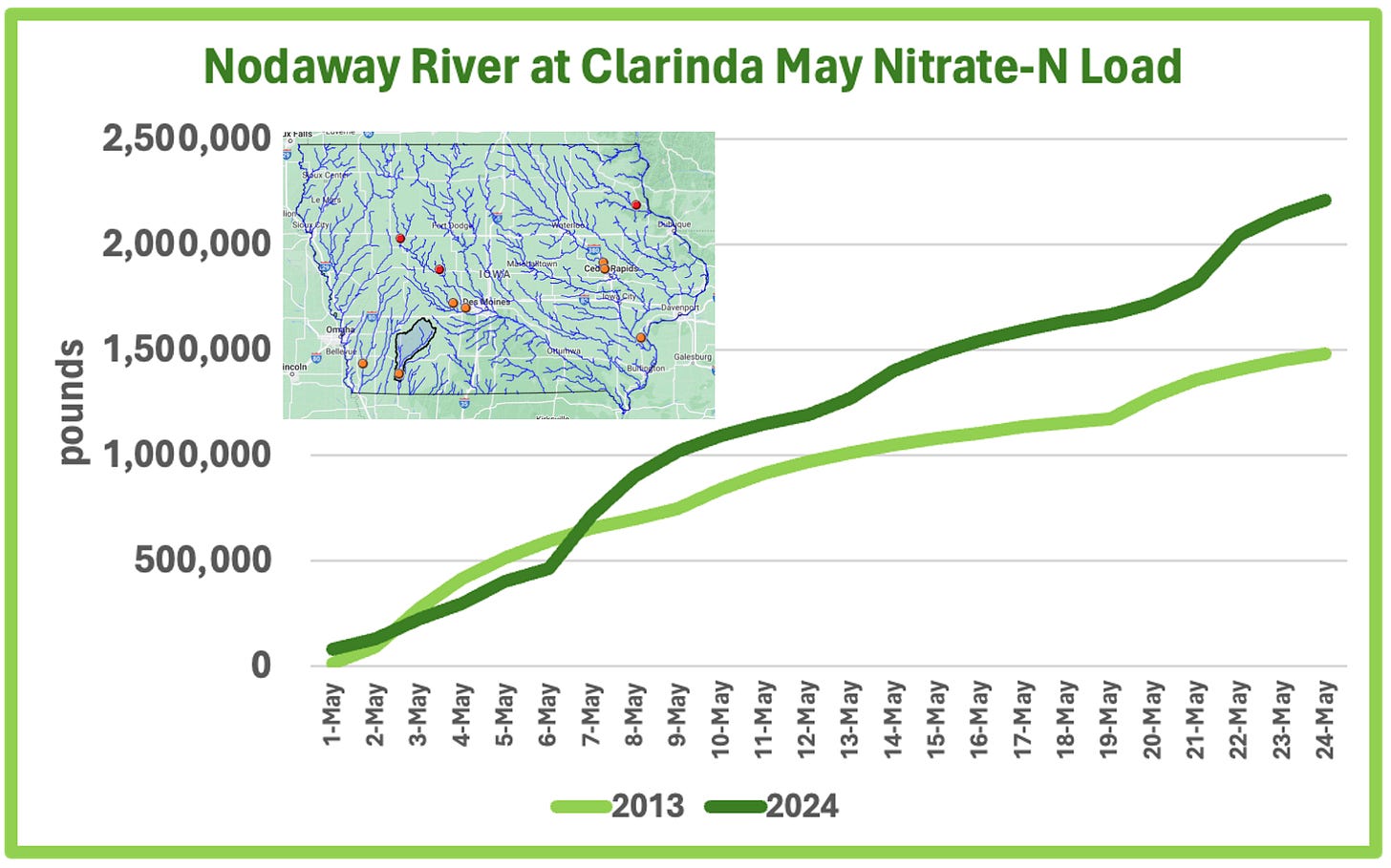

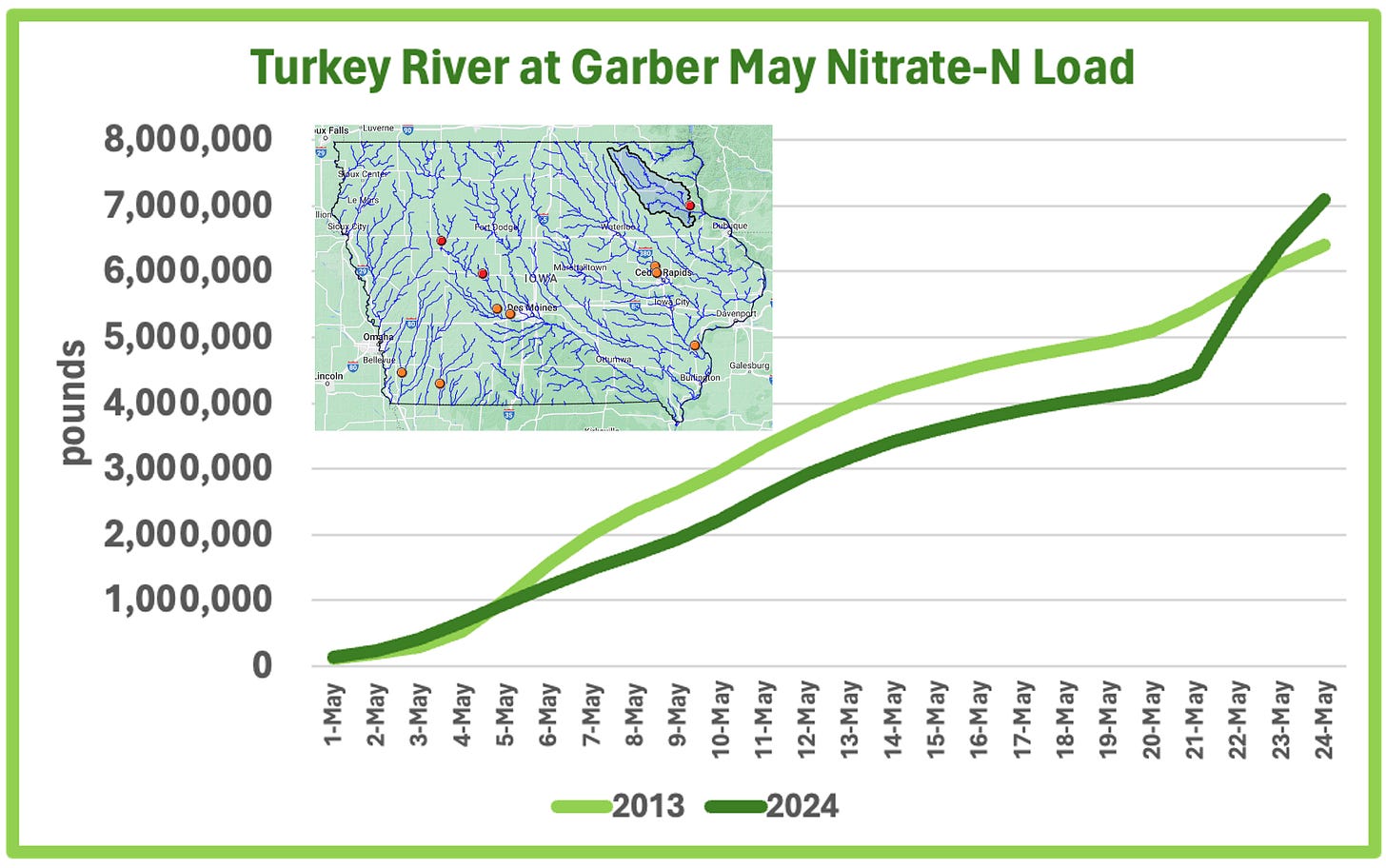

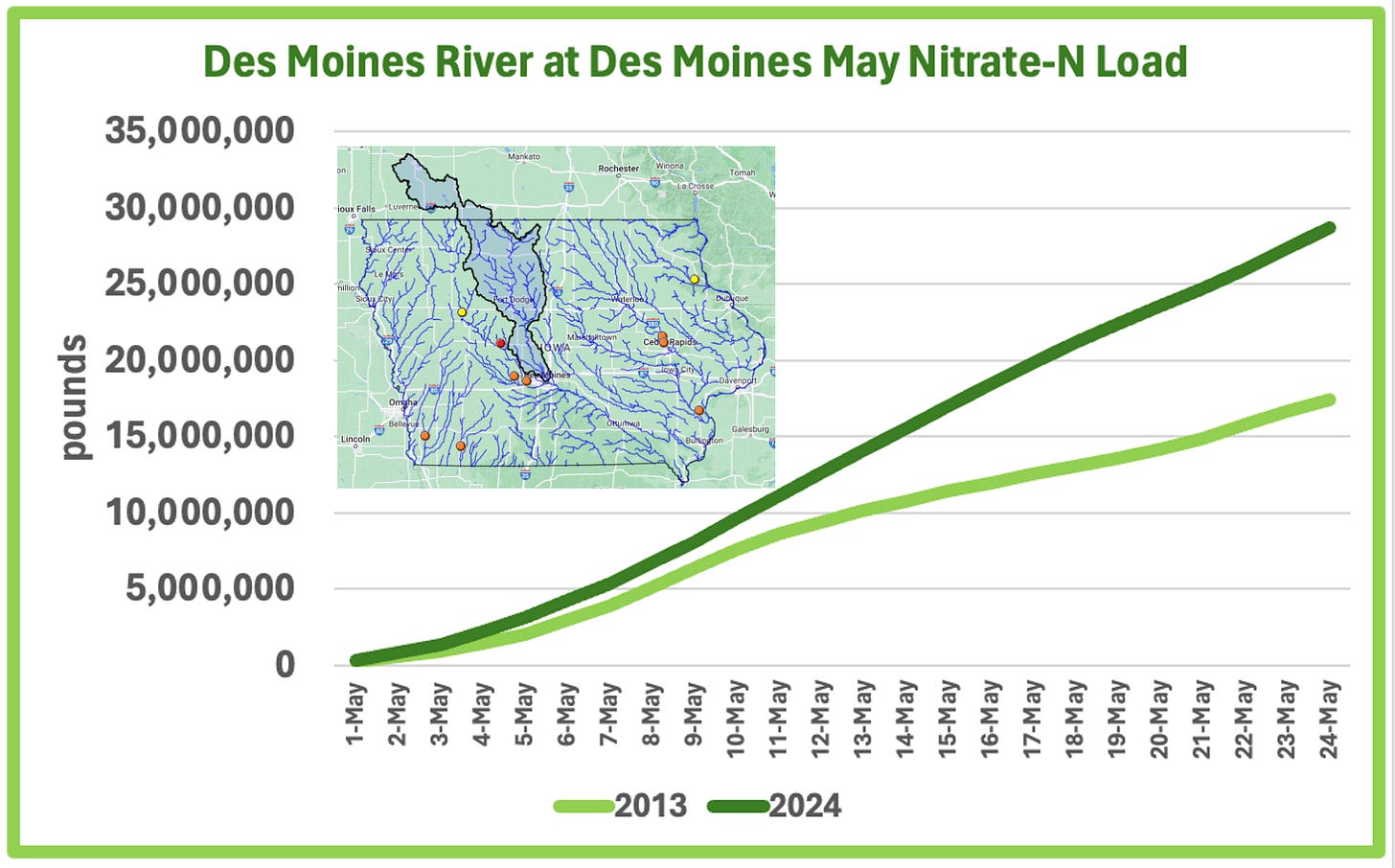

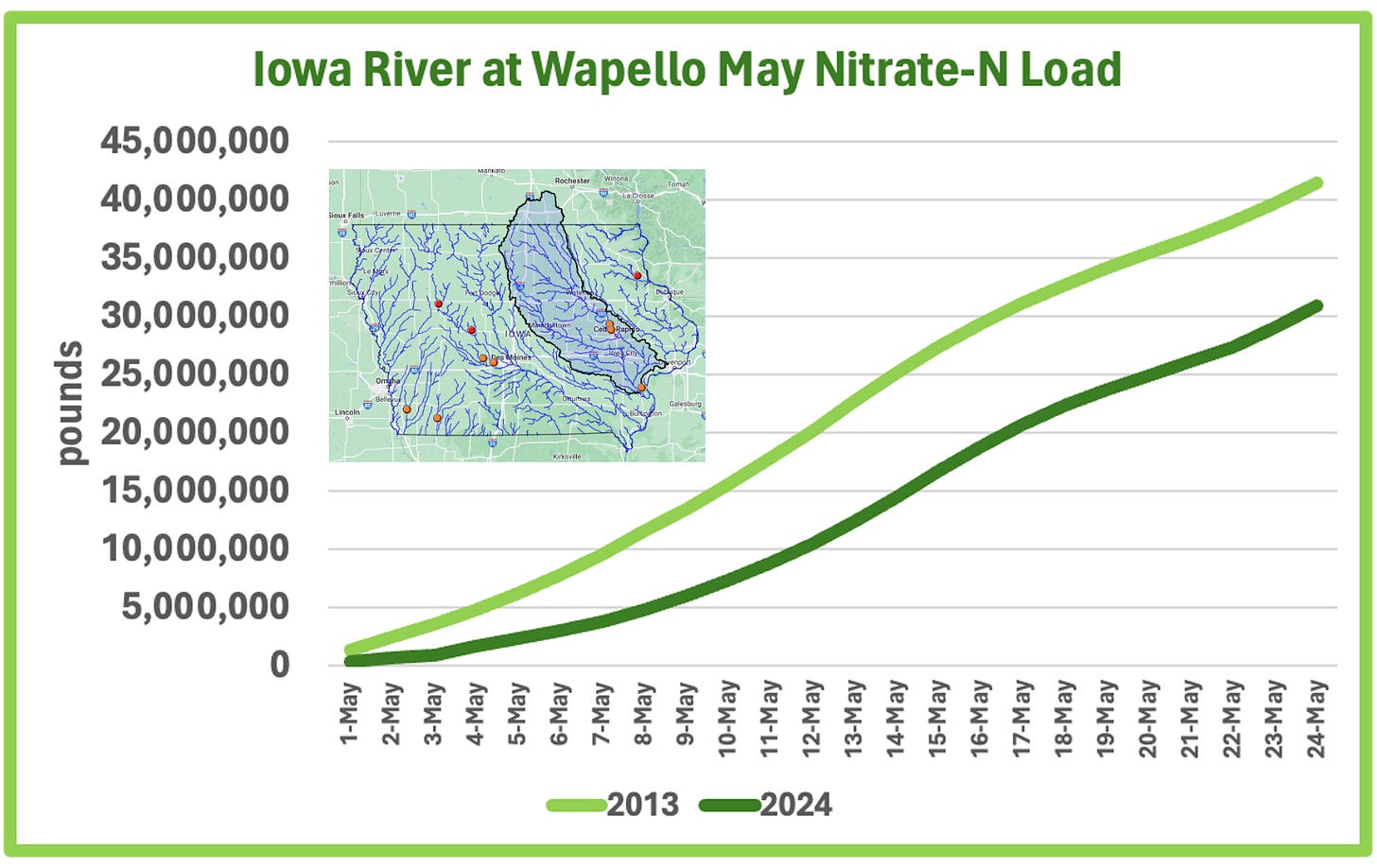

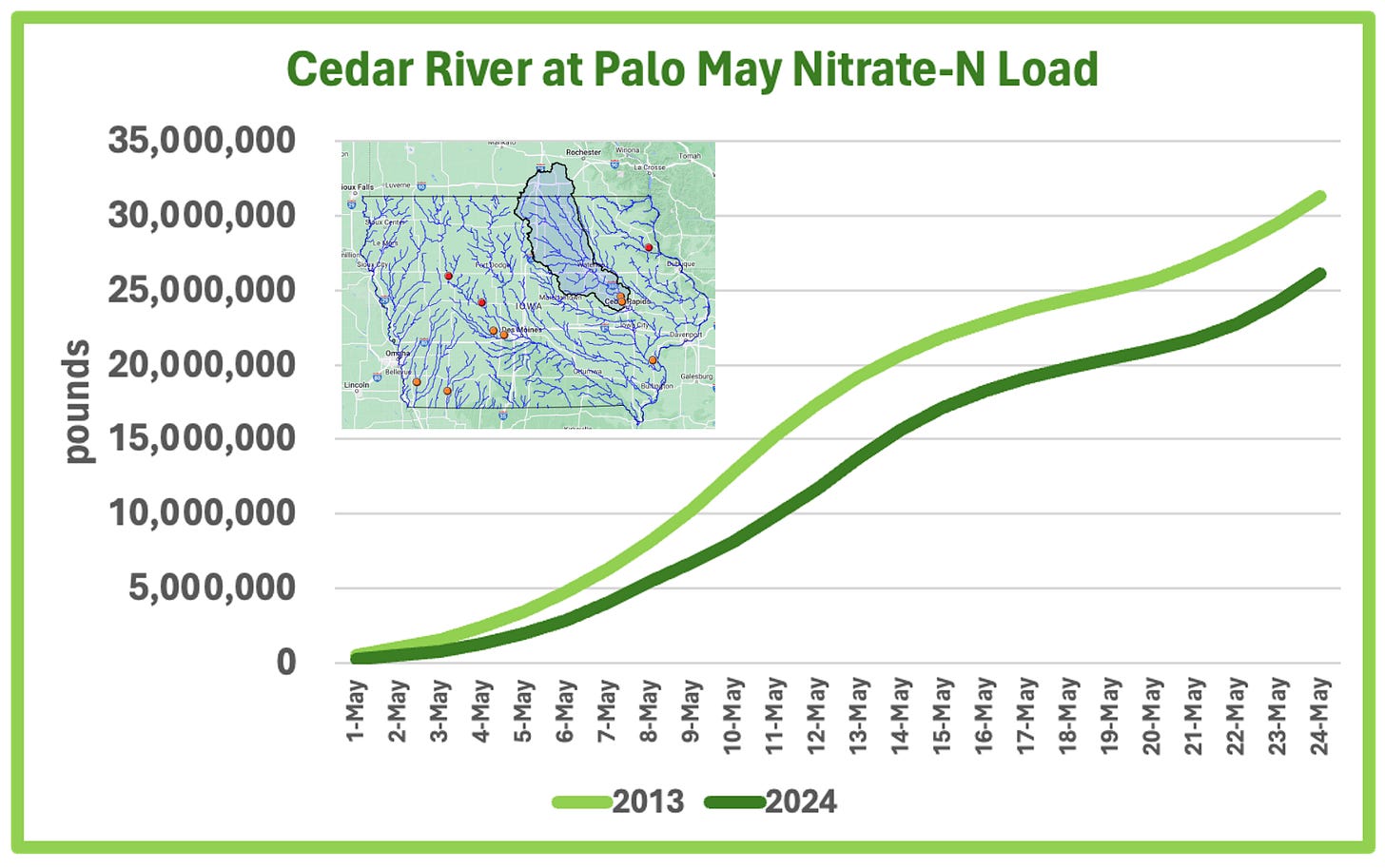

Right now, Iowa is amid a nitrate loss event that is unmatched in the state’s history, with the possible exception of May 2013. The 2024 stream concentrations are modestly lower than 2013, but the loads are near the equal of or even greater than 2013, as the graphs at the end of this post illustrate. All data is from U.S. Geological Survey stream sensors with the exception of 2013 Des Moines River data, which was generated by the Des Moines Water Works laboratory.

The 2013 event was big news because the man agriculture despised, Des Moines Water Works General Manager Bill Stowe, used his bully pulpit to make it big news. With Stowe dead several years now, there’s been much less coverage of this year’s stream condition, and there’s likely some fatigue among the public on this issue. (Kudos to Jared Strong and Erin Jordan for writing tirelessly about water quality.)

As Stowe found out, to talk about this invites retaliation from the ag industry, farmers and the legislature, even though the tired responses from farmer and industry types are the exact same ones they’ve been using for the past 40 years—we can’t help it, we don’t want to lose our nitrogen, it’s the golf courses and the sewage plants, we’re feeding the world, etc. To engage farmers and the industry from the environmental side on this topic literally requires degrading yourself to no small extent, such is the adolescent level of discourse you must endure.

But alas, people far more important than me have decided this pollution doesn’t matter for much—USDA under both D and R administrations; Iowa state, county and local governments; public health institutions; agribusiness titans and farmers. It doesn’t matter much, anyway, compared to the production of junk carbohydrates and vehicle fuel that generates it and the millionaires that benefit from it.

I mean this in all seriousness—there’s a real cult surrounding the nitrogen fertilization of corn. Someone from Iowa State once told me that the definition of an agronomist is somebody that has an unquenchable obsession with a plant’s response to nitrogen. They probably should have added “at the expense of the larger community.”

You might recall ISU president Wendy Wintersteen making a widely reported comment about helping young, white and rural men feeling comfortable at ISU. Sometimes I wonder if this involves some kind of nitrogen initiation ritual that bonds graduates of the University’s College of Agriculture to each other with the oath “Thou shalt not underfeed thy corn.”

I am convinced this pollution matters: for nature, for economy, for conservation, for people. So, I’m going to turn the steering wheel hard here: I’m also convinced our institutions not only tolerate it, but bless it, because it’s generated by a landed gentry of old, white males (>99% of Iowa farmers are white). If people of color were generating this pollution, it would be the environmental crime of the century.

Knockout punch: "I am convinced this pollution matters: for nature, for economy, for conservation, for people. So, I’m going to turn the steering wheel hard here: I’m also convinced our institutions not only tolerate it, but bless it, because it’s generated by a landed gentry of old, white males (>99% of Iowa farmers are white). If people of color were generating this pollution, it would be the environmental crime of the century."

Every day, many timese per day, the air waves remind us that farmers feed and fuel the world. In the same breath, we hear farmers just can't make it on their own because of high input cost, crop pressures, and unfair world competition. This leads me to believe without tax payer subsidies, they could not even feed themselves. This diversion takes the light off who the real polluters are. Sure, the IDNR, IDALS, NRS, NRCS, etc. give comfort to farmers for their transgressions but it doesn't change the facts. Overapplication of fertilizer is driven by greed, ego, and fear. Not my idea of an American Hero.