President Ralph Kramden announced Saturday (2/1/25) that the U.S. was slapping a 25% tariff on all goods from our closest ally, Canada. Pow, right in the kisser, Justin Trudeau. Ralph says we have all the lumber and oil that we need and that if they don’t like it, Canucks can just erase their southern border and become part of the U.S. A reasonable person might say this would be akin to moving your furniture into a house ablaze, thinking at least it’s warm in there. Donald I mean Ralph probably sees all sorts of geographical renaming opportunities, after all there’s a big roundish water body in the middle of Canada eerily similar to the Gulf of Mexico I mean America in size and shape, Hudson Bay. A perfect place for the Trump brand to decorate maps, right in the middle of the Canada, just to the north of Dontario.

Trump has told Americans to expect some inflationary pain as result of the tariffs. I am bewildered by this curious strategy of intentionally inflating the cost of living, mere months after bashing Biden on inflation, but I’m bewildered by a lot of things.

If you bought a bunch of oats or products containing oats (Cheerios, for example) prior to Saturday—lucky you. A lot of U.S. oats come from Canada, making Trump a cereal killer, I suppose. This includes the ones processed at the world’s largest oat milling facility—Quaker Oats in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. And thus begins our story.

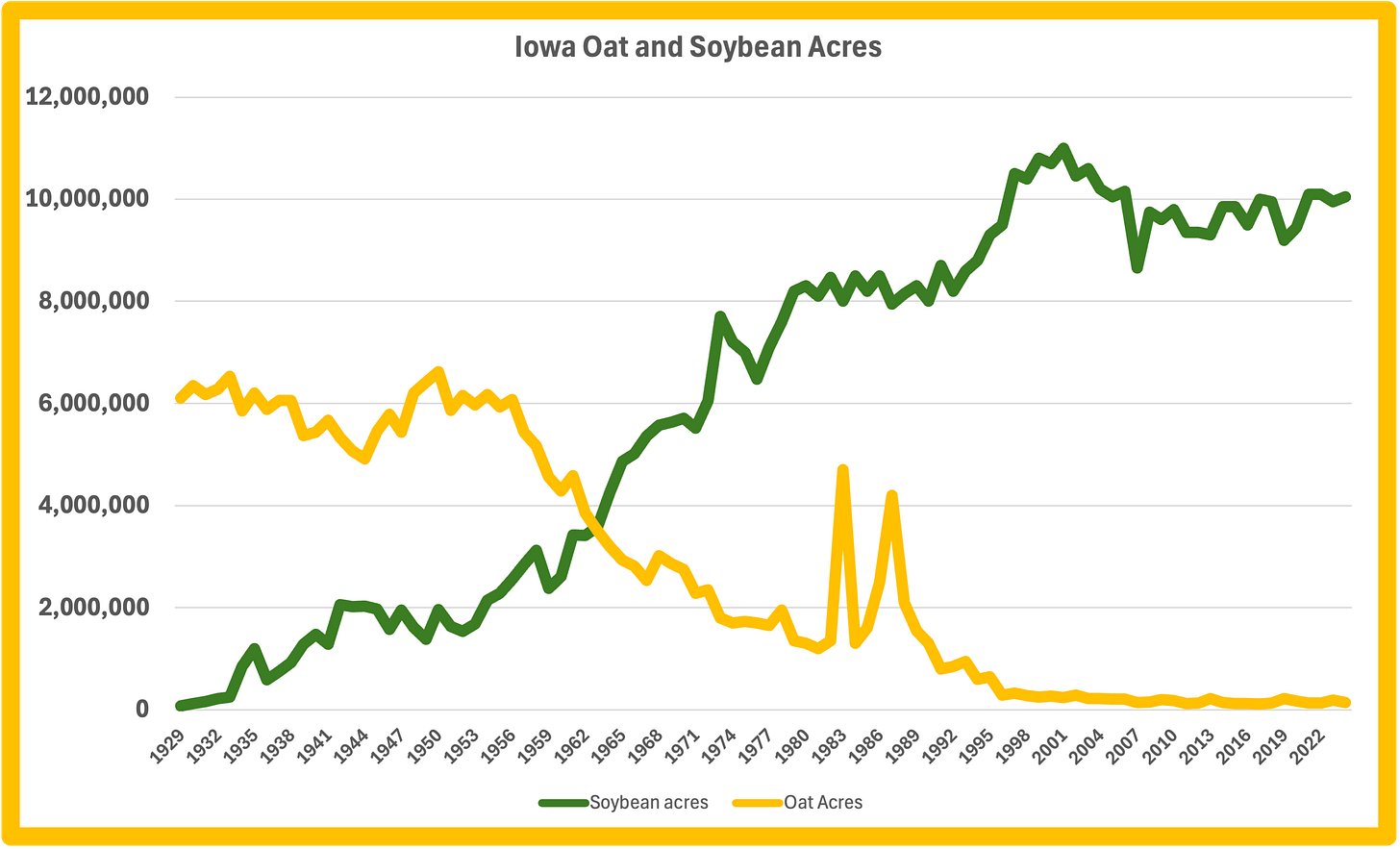

Iowa was once the top oat producing state in the U.S., regularly growing 20% of the U.S. crop. But now we usually lag the Dakotas, Minnesota and Wisconsin in oat production although Iowa was uncharacteristically 2nd to North Dakota in 2023 (1). After peaking at 274 million bushels in 1948, Iowa oat output dropped precipitously in the 1950s and 60s with the emergence of soybeans as a second cash crop. Yield has sunk as low as 2 million bushels in 2018, less than 1% of the peak. Iowa’s share of the U.S. crop has ranged between 4 and 13% over the last 10 years. For reference, Iowa produces about 18 and 14% of the U.S. corn and soybean crops, respectively.

Quaker in Cedar Rapids mills about 2 million pounds of oats per day. Making some assumptions about bushel weight, this would be about 19 million bushels per year, less than 10% of peak production (1948) in Iowa. This illustrates that most of our oats were not eaten by people but were fed to animals—food animals yes, but also beasts of burden like horses and mules. By 1950, most Iowa farmers had a tractor and oat production decreased steadily thereafter. As soybeans started to displace oats and other non-corn crops, the stage was being set for the transition of livestock from diverse and integrated crop and animal production systems to CAFOs. Hogs and laying chickens eating soybeans grow fast and the country began using soy oil for cooking.

Oats were often grown in rotations that included three or more crops—corn, alfalfa, clovers, perhaps some wheat and barley, and sorghum. These ‘extended’ rotations help suppress weeds and insects. Condensing the rotation to only two crops (corn and soy, and sometimes only corn) left Iowa’s systems more vulnerable to pests. The post-WWII chemical industry stepped in, and in just 5 years (1947-52), USDA registered 10,000 new insecticides (2).

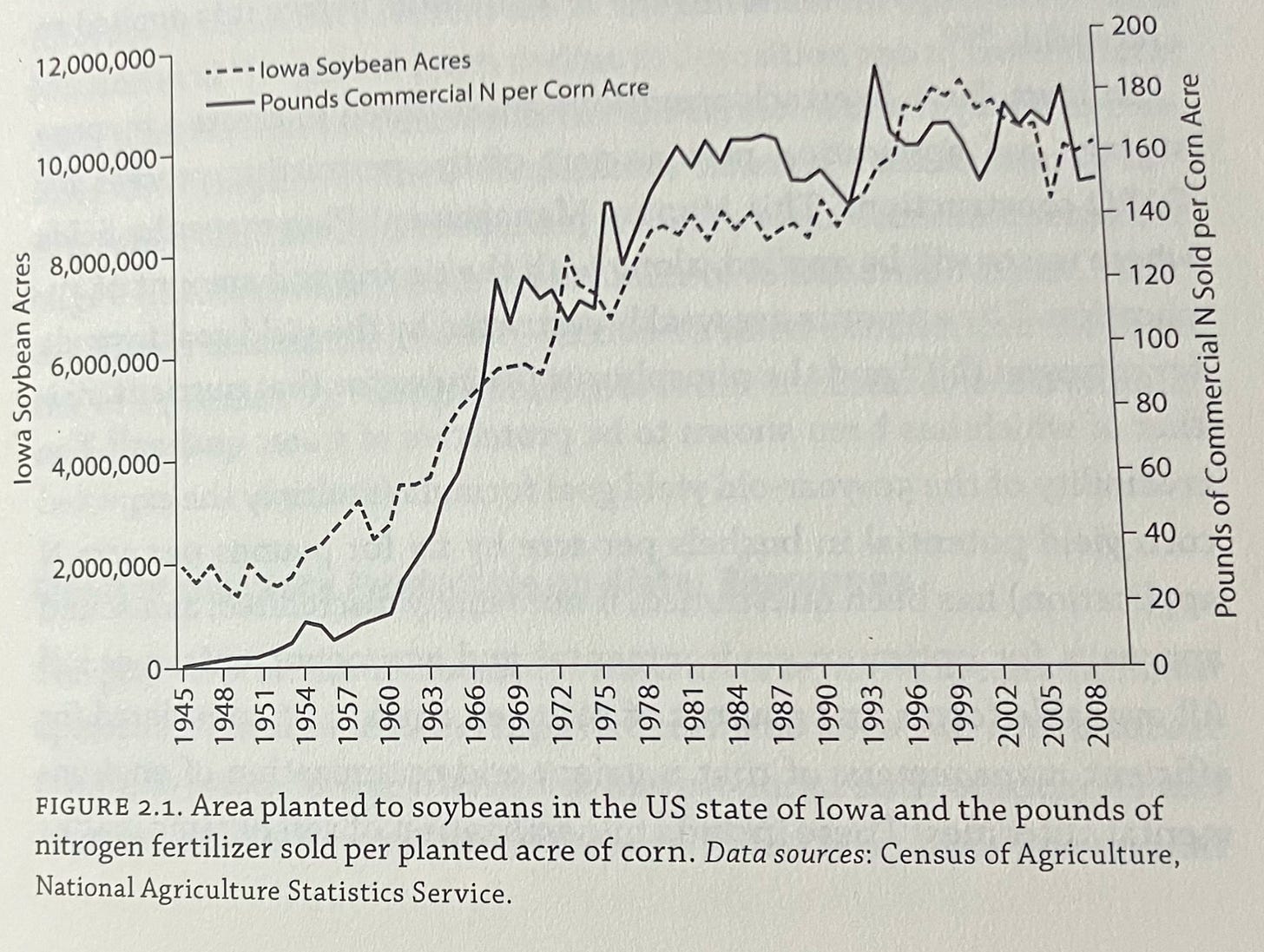

The oats to soybean transition also ushered in the need for chemical fertilizer. Manure and nitrogen-fixing bacteria symbiotic with alfalfa and clover provided all the corn nitrogen inputs for most farmers prior to 1950. Nitrogen fixing bacteria also are symbiotic with soybeans, but the amount of nitrogen fixed is unpredictable and insufficient for corn in most circumstances. Thus, while soybeans shepherded livestock into CAFOs they also left crop farmers needing chemical formulations of nitrogen for corn. That is most commonly anhydrous ammonia in the present day. The average amount of chemical nitrogen applied to an acre of Iowa corn increased from 16 pounds to over 120 pounds from 1960 to 1968 (3).

An old adage: when cows go out, soybeans come in.

You just read how the fossil-fuel based Farmkenstein monster was created. It has no appetite for oats.

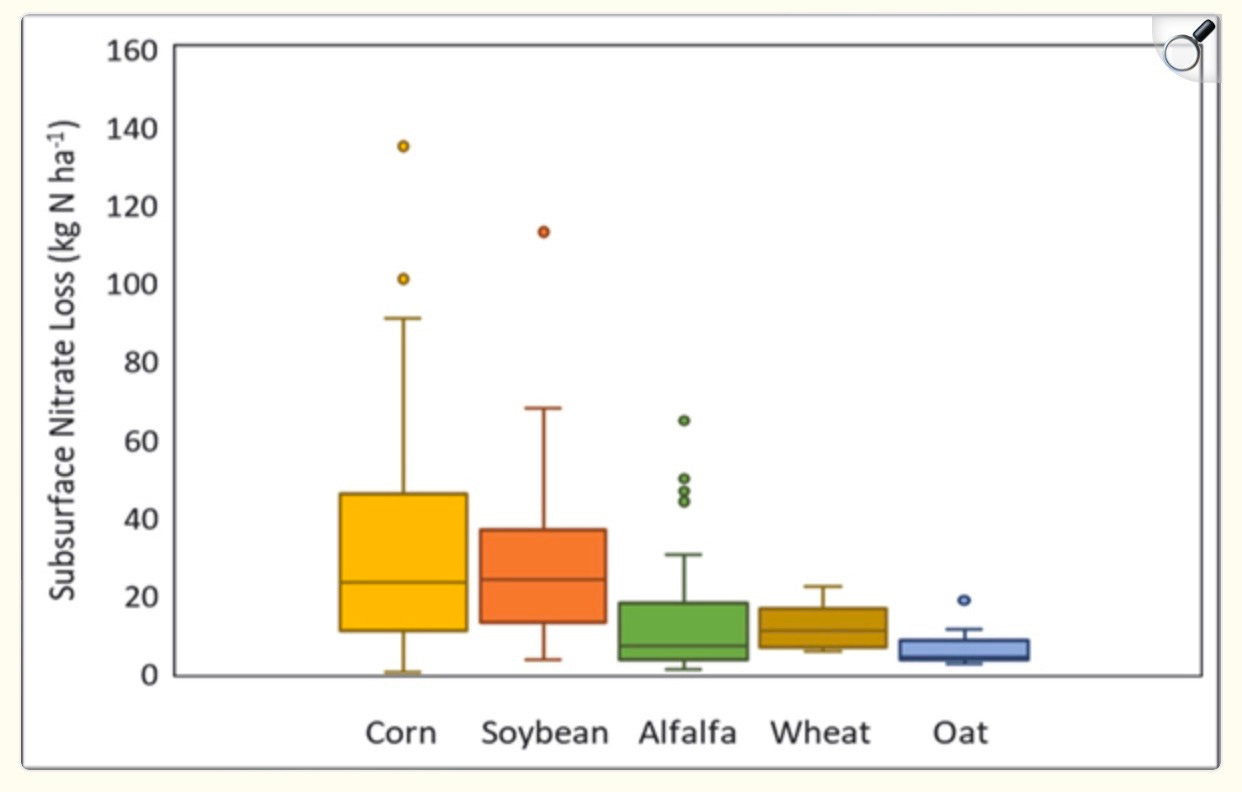

I co-authored a journal paper in 2009 (4) that showed displacement of oats with soybeans went in lockstep with an increase in nitrate pollution in Central Iowa’s Raccoon River, the source of drinking water for the Des Moines metro. Oats are planted in early spring; soybeans in late spring. In that 4-8 week interlude, Iowa gets a lot of rain while there’s nothing growing in a field intended for soybeans to sequester nitrogen left behind from the previous years’ corn crop, and that’s an important source of water pollution in Iowa. Oats, however, are vigorously growing in April and May and using both water and nitrogen. For this and other reasons, the environmental outcomes with oats are far better than with either corn or soybeans.

Similarly Matt Liebman, retired Henry A. Wallace Endowed Professor of Sustainable Agriculture at Iowa State, studied oat-inclusive crop rotations throughout his career and found these rotations required far less nitrogen inputs (i.e. fertilizer), lost less nitrogen to streams and aquifers, produced more biomass, had fewer pest pressures, and resulted in less soil erosion and lower greenhouse gas emissions, when compared to a corn-soy rotation (5).

This brings us back to Quaker and the tariffs. Why is Quaker using Canadian-sourced oats, and why aren’t Iowa farmers growing more of them when the world’s largest oat mill is right here in the front 40? The answers to these two questions commingle and are difficult to untangle from one another. Many people have approached me at my programs with their own thoughts on this subject, so some of what follows may be hearsay.

Quaker may prefer Canada oats because the conventional wisdom is they have a higher ‘test weight’, meaning a bushel of oats from Canada weighs more than a bushel of oats grown in Iowa. In talking to farmers, I have heard that the test weight of Canada oats is around 38 pounds while Iowa oats run about 32. Liebman thinks Canada farmers may be adept at ‘blowing off’ low weight oat kernels during harvest, in effect increasing the weight of a bushel. Weather and planted varieties may also contribute.

Many believe Iowa nights are now too warm and humid for optimal oat growth. But Practical Farmers of Iowa (PFI) has been renting Iowa State research farm space to work on this (studying oat production at ISU isn’t exactly in vogue) and they have demonstrations showing an amazing yield of 125 bushels per acre (Iowa average-86; Canada average-89) with a test weight of 36 pounds per bushel. There is no doubt these numbers can compete, if not blow away, Canada-sourced oats.

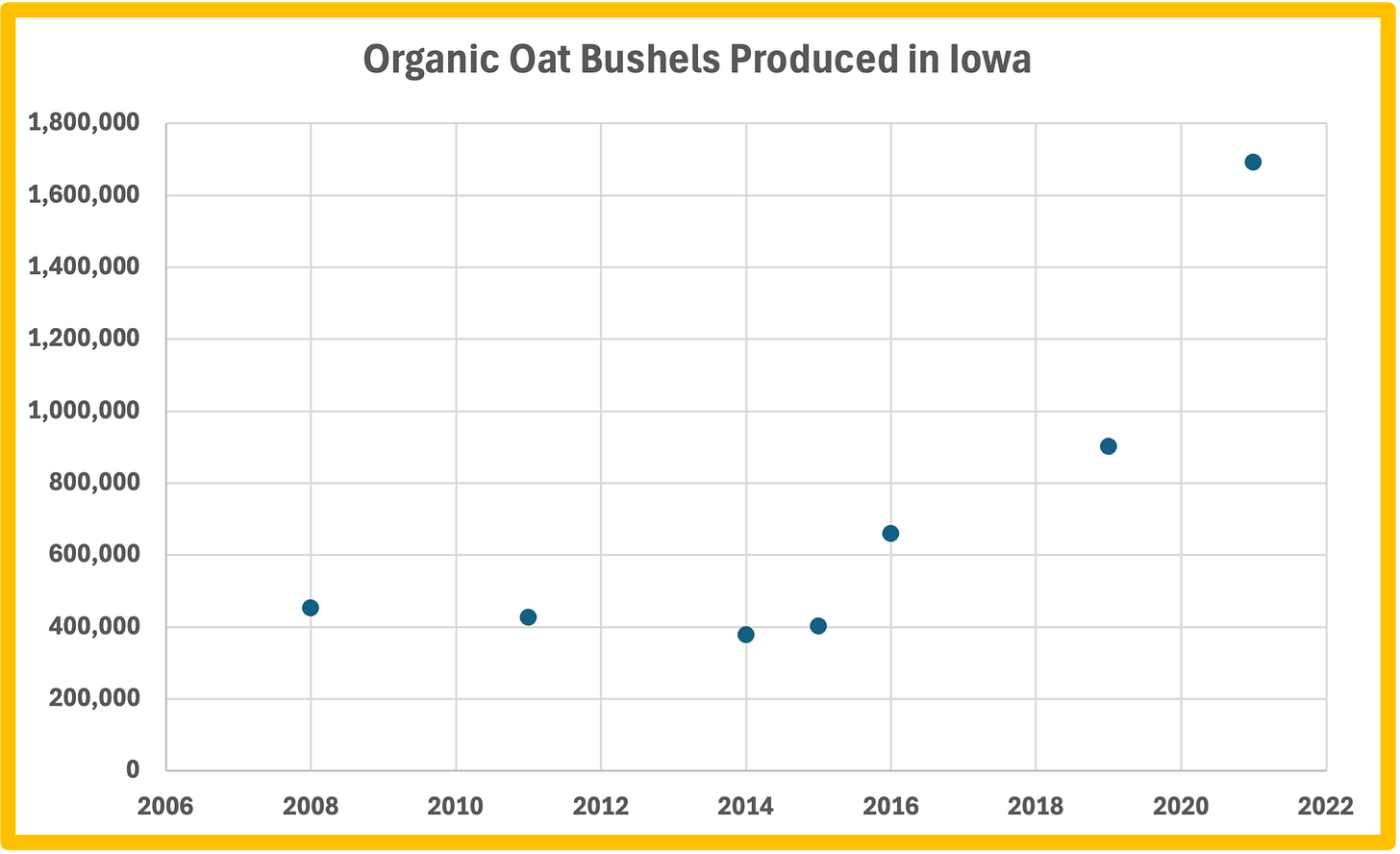

Oats have long been a favored food for people seeking a healthy diet. If you follow the ‘homesteading’ craze on social media, you’ll quite often see these folks incorporating organic oats into their diet. There’s a perception out there that conventional oats are brought to market generously sprinkled with glyphosate (Roundup), this applied just before harvest to help uniformly ripen and dry the grain. There is no doubt this has been happening in Canada, although there have been efforts in recent years to end the practice. Quaker does not deny their oats may contain residual glyphosate. Interestingly, the uptick in Iowa oat production in recent years is largely because of an increase in organic oat production, which would not include the use of glyphosate.

To finally circle back to Ralph Kramden, with a stroke of the Sharpie cradled within his baby hands, he effectively raised the test weight and yield of Iowa oats 25% with the tariff. It seems to me a huge opportunity exists for Iowa farmers wanting to grow a crop that people can actually eat and doesn’t kill us with its pollution. Farmers probably need Quaker’s help, however, to make it happen. When thinking about this, my mind keeps coming back to the fact that Iowa legislators and Governor Kim Reynolds required every gas station in Iowa to sell corn-based e-15 blended fuel. Why can’t we make something similar happen for oats?

PFI has a goal of 1 million oat acres. I’m telling you here and now that I believe 1 million oat acres would clean up our water more than ALL the conservation implemented since the birth of Iowa’s Nutrient Reduction Strategy in 2013, especially if those acres were targeted toward environmentally sensitive areas like Northeast Iowa, which also happens to be the area of Iowa most climatically suited for oats. The only reason we couldn’t make this happen is because the political and economic establishment won’t let it happen.

Why wouldn’t they want it to happen, you may ask? Well, oat production requires less expensive seed, less fertilizer, less herbicide, less insecticide, less fungicide, less grain drying, cheaper crop insurance and I suspect cheaper machinery, all stuff the agribusiness titans want to sell. That’s why.

If there’s a governor or secretary of agriculture candidate out there that’s got some moxie and thinking about an environmental or economic platform, I hope they’re reading this now.

Finally, I want to put a plug in for one of my subscribers, Minnesota farmer Kevin Connolly. He’s an oat man. There are probably several others and if they leave a comment I will mention them at the next post.

Reference Material

1) USDA Census of Agriculture, Quickstats.

https://quickstats.nass.usda.gov

2) Stork, Gocke and Martin, 2007. The Golden Age of Pesticides.

3) Merchant, J. and Martin, R. eds., 2024. Industrial Farm Animal Production, the Environment, and Public Health. JHU Press, p. 17.

4) Hatfield, J.L., McMullen, L.D. and Jones, C.S., 2009. Nitrate-nitrogen patterns in the Raccoon River Basin related to agricultural practices. Journal of soil and water conservation, 64(3), pp.190-199.

5) Liebman, M., Graef, R.L., Nettleton, D. and Cambardella, C.A., 2012. Use of legume green manures as nitrogen sources for corn production. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 27(3), pp.180-191.

6) Koropeckyj-Cox, L., Christianson, R.D. and Yuan, Y., 2021. Effectiveness of conservation crop rotation for water pollutant reduction from agricultural areas. Transactions of the ASABE, 64(2), pp.691-704.

You might find this podcast from Damian Mason where he interviews a couple of Canadian Farmers about growing oats interesting. https://youtu.be/kOE0ygdqND0?feature=shared

Here in Western NY, I can attest that oats are not grown for grain as much as they were when I started my career 30 years ago. Most of the oats here go to horse feed for our amish community. Even organic growers have gotten away from them.

We have been in a weather pattern the last number of years where the springs have been too wet to plant oats timely which is important for yield and summer annual grass weed control.

Technically spraying oats with glyphosate pre-harvest is off label but there is no doubt it is done. What would really push farms to diversifying their rotations is to make growing corn less profitable by getting rid of subsidies: ethanol, crop insurance, disaster payments, etc.

I really enjoy your writing even though it is often critical of the agricultural industry I am part of.

Iowa oat fields also used to raise a LOT of pheasants!