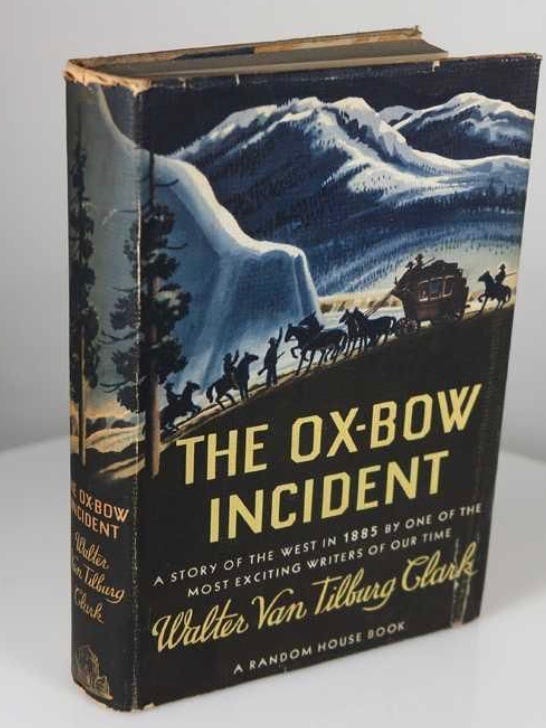

Walter Van Tilburg Clark’s first novel, The Ox-bow Incident (1940), has often been characterized as a Western adventure story in the vein of Louis L’Amour or Zane Grey, but there’s more to think about in Clark’s short novel than in the entire combined body of work of L’Amour and Grey, which of course is voluminous. [Spoiler alert: I give away the ending of Ox-bow here, so in the unlikely circumstance a reader of this essay owns an unread copy, be forewarned.]

The story’s two protagonists, itinerant cowboys Art and Gil, ride into the town of Bridger’s Wells, where they are not unknown but also not well-known. Shortly after arriving, a local ranch hand rides into town and deliriously tells a second-hand story of the murder of a well-liked cowboy (Kinkaid) and the subsequent theft of cattle from the valley’s most prominent rancher (Drew). The town’s respected sheriff is absent and in fact is reported to be at Drew’s ranch, an hours’ long ride away.

The deputy sheriff (Mapes) pulls an “I’m in charge here” and begins to unlawfully assemble a posse to track down and punish the murderers, ignoring warnings from the town’s judge. After much deliberating, the posse begins to break up and retire to the saloon, but Tetley, an aloof ex-Confederate Colonel, arrives with information provided by his Mexican ranch hand “Amigo” about the whereabouts of three or four men who may be the murderers. Although not well-liked, Tetley convinces the group that justice will be slow or even non-existent if the criminals are caught and brought before the judge, who is seen to be corrupt. The posse reassembles.

Art and Gil join the posse of 27 men and one coarse and unfeminine but admired woman (Ma), mainly because they fear they will be accused of the crime if they don’t join. The posse also includes Tetley’s effeminate and troubled son, Gerald, forced to join against his wishes by his tyrant father, and Davies, one of the town’s established and successful businessmen. Davies is against the posse and vigilante justice but joins to try to head off a lynching. Tetley assumes control of the group almost by default, but also through some clever flattery of Deputy Sherriff Mapes.

The group travels through treacherous mountain terrain after dark during a spring snowstorm to eventually capture three men and 50 cattle just after midnight in a small mountain meadow known as the Ox-bow. The three are led by an aspiring young rancher, Martin, who has hired a senile Civil War veteran (Hardwick) who may also be suffering from what we now consider PTSD, and a tough, taciturn Mexican cowboy with a sketchy past, possibly named Martinez. Martin has a wife and two children living on small ranch a short distance away.

Tetley makes a hollow attempt to question the three captured men, but almost everyone (including the three) knows their fate is pre-ordained. Martin claims he bought the cattle from Drew and that they know nothing of the murder. A vote of the posse is taken, and it is 23-5, guilty. The five include Tetley’s son Gerald, Davies and a former slave and preacher named Sparks. Gil and Art both vote with the majority to hang the three.

Martin is allowed to write a letter to his wife prior to the hanging, and Davies promises to deliver the letter. Davies also quietly implores the group, one by one, to read the letter because it he thinks it proves the three’s innocence. No one will read the letter. During this letter writing interlude, Martinez tries to escape but is shot in the leg and captured and is found to have possession of the murdered Kinkaid’s pistol. Martinez says he found the gun on the trail. This is the only piece of evidence the posse has of the alleged murder and it comes after the three were already condemned. It gives many of the posse comfort that the right decision has been made.

Martin, Hardwick and Martinez are noosed and brought to a lightning-struck pine tree and stood upon their horses so that they can be hanged at sunrise. Gerald is forced by his father to be the one to whip Martin’s horse when the signal is given. At the signal, Gerald botches the task and Martin’s horse only slowly walks away, leaving him to strangle. The other two die instantly. The dangling Martin is eventually shot to end his suffering.

On the way back to town the Posse encounters a group of four men—the Sheriff, the Judge, Drew the prominent rancher, and the alleged murder victim, Kinkaid, slightly injured from fighting off rustlers, but otherwise alive and well. Upon hearing of the lynching, the Judge orders the Sheriff to arrest the 28, but after silently deliberating for several minutes, the Sheriff refuses. He deputizes 10 of them to help pursue the rustlers that injured Kinkaid. The rest return to Bridger’s Wells.

Only two of the 28, almost all of whom are well-respected members of the community, express any serious remorse for the lynching—Tetley’s son Gerald, who hangs himself, and Davies, who wallows in self-pity and begs off delivering the letter to Martin’s widow. Ironically, both voted to acquit the condemned three. Tetley also commits suicide upon hearing of the death of his son. Gil and Art, both otherwise likable and honorable, if a little rough around the edges (especially Gil), simply want to get out of town. It’s clear Art sees dying an honorable death as more important than whether the sentence was deserved; all three of the condemned men, and especially Martin, made desperate and emotional pleas to be spared and Art saw this as undignified and cowardly.

Although the book was made into an Oscar-nominated movie (Henry Fonda and Harry Morgan as Gil and Art, respectively), it makes no “great novel” lists as far as I can tell. Good Reads doesn’t even list it in the top 659 American novels. Omission from the “great” lists is likely because many throw it into the L’Amour/Grey genre. The prose is not great but there’s little opportunity for it in a book of this sort. The writing is incredibly precise and suspenseful, and Clark does an excellent job writing dialect, which is not easy. Wallace Stegner loved the book and Clark’s writing in general, and that is how I came upon it. But Clark clearly had something larger to say here, and so what was it?

Stegner thought Clark was rejecting the phony and overdone machismo of the American West, and our worship of that myth. But Stegner also said something about the book that resonated with me: “Evil has courage, good is sometimes cowardly.” Evil in the book is represented by Tetley; good, or a weak version of it, is represented by Davies. Davies is burdened not by the deaths of the young husband and father and his two cohorts, but by his own cowardice in not physically confronting Tetley. Tetley, while evil, had the courage to see it through to his final objective; Davies, while on the side of good, did not, and didn’t even have the courage to face Martin’s widow.

Another unmistakable theme of the book (in my opinion) is how guilt and culpability and maybe even dignity vaporize like dew in the desert sun when wrongs are committed collectively by “good” people, and especially when they’re members of our own community. Had Tetley alone committed three murders, there’s little doubt the Sheriff would’ve slapped the cuffs on him. But the fact that 28 (or 23, as the case may be) were culpable, the Sheriff let them all off. The dignity that the posse derived through a lens of law and order disintegrated once the vote to condemn had been taken. The group quickly begins to get drunk and eat the condemned men’s food while one of the posse even clumsily tries to seduce Ma as the three were being prepared for the hanging.

The topic of Louis L’Amour’s writing was the American West. As Stegner said, Clark’s topic was civilization, and his raw material was the American West. You certainly must know by now what the topic of my writing usually is. And even though Iowa is an embarrassment of riches for me when it comes to raw material, I still need to look for inspiration almost anywhere and everywhere, including in 1940 novels. Maybe this endless search causes me to see allegories and parallels where they don’t exist, who knows. But I’m always looking for them.

As lifelong professional writers go, Walter Clark was not prolific. He wrote four novels and a few truly great short stories, and then devoted much of the rest of his life to teaching. When I read his work, I’m reminded of what Larry McMurtry said about fellow writer and Texan John Graves, that is, “everybody thinks Graves is so great because he never published his failures.” I admire someone with that kind of self-awareness and the courage to trust it.

Read the Ox-bow Incident when I was 14 for a Jr. High school report, it made a big impact on me. Thought me to not "get along and go along with bullies and influencers". A very good lesson for all who live in Iowa. If we had followed some of these lessons, we may not be in the mess we are in now with such atrocities as Iowa's water quality, air pollution, horrible land use policies and the rampant destruction of our natural areas. The bullies in the Iowa House, Iowa Senate and Iowa Executive Branch of State Government are leading us down the slippery path of an unlivable environment. No wonder why Iowa's young people get their education and leave adding to the brain drain. Let's not talk about the fact that Iowa has one of the highest cancer rates in the nation, per capita. Yes, getting along and going along with horrible leadership in Iowa is as far from "Iowa Nice" as we can get.

Thanks, Chris, for your comments. You once again know how to use analogies to highlight the simple truth that bites us in the rear each and every time. Best to you, Bill. (And the old black and white movie isn't bad to watch either!)

Thanks for sharing this Chris! "Group think" and the "courage of evil" are certainly very relevant and timely topics. Somewhere back in my early childhood, one of my elders offered this wisdom: "Wrong is wrong, no matter how many may try to convince you it is right". It helped guide my career in science and in a science directed career - looking for facts - and objective, evidence-driven truth. I know that your work and passion are likewise guided. It can be a long and difficult path to walk, when going along to get along is so much easier and often the norm.