You’re reading my inaugural post at Substack. I’m here now because a few farmer legislators here in Iowa couldn’t stomach my blog at the University of Iowa domain, so they made me an offer I couldn’t refuse: take it elsewhere, or else. I’ve started over several times in my life and so I suppose one more restart can’t hurt.

I was told one time by a legislator that I could fearlessly write about anything except environmental justice. I happen to think that a little fear can enhance a person’s writing so I took that as an invitation. The first one of those, titled Environmental Injustice, inspired a Fayette (IA) Farmer who spends his springs at the Iowa capital to send an email to my bosses suggesting I should do some self reflection. A hard copy of the second justice-themed post, God Made Me Do It, was in the hands of another furious farmer about a month ago when I was asked to leave the university’s domain. That one forms the basis of this post here.

I feel compelled to tell you before you read on that this Substack will not be a regurgitation of my university blog. There will be new stuff, I promise. But this one serves as bridge to from there to elsewhere, and I think it was one of my best at the old site.

From Carl Sandburg’s book/poem, The People, Yes (1936):

“Get off this estate.”

“What for?”

“Because it’s mine.”

“Where did you get it?”

“From my father.”

“Where did he get it?”

“From his father.”

“And where did he get it?”

“He fought for it.”

“Well, I’ll fight you for it.”

The ag communication shops are the answer to all my prayers when it comes to inspiration. I read something a month or so ago from one of them and I knew I had to write about it, but it took a while for an idea to tassel out. The piece profiles an Iowa farmer who apparently is on a mission from God to grow corn and soybeans. Most human beings, including the one writing these words here, try to derive some meaning from their existence and so I don’t fault that if that is the angle. I did, however, find this quote revealing: “If you can raise more corn and beans on this acre of ground the good lord gave you, you darn well better be doing that.”

As far as God giving “us” the land, there’s a few descendants of a continental-scale genocide that would like a word regarding this farmer’s god. But ignoring that for the moment, yes, it’s true enough that you can raise a lot of corn and beans on Iowa land, and a lot of other stuff that we don’t grow anymore: oats, apples, vegetables, oak trees, and so on. And rest assured if corporate CEOs wanted Iowa farmers to grow that other stuff instead of corn and soy, that is what they would be growing, and God could just go pound sand. You gotta know who's the boss, after all.

I do find it interesting that agriculture apparently is looking to God for endorsement of what we’ve done to this corner of His earth. If you’ve been part of a system that extirpated three ecosystems, straightened and ditched thousands of miles of streams, drained millions of acres of wetlands, felled the great pine, oak and walnut forest of the northeast corner and killed off part of an ocean 1500 miles away, mainly so we could save a nickel on a gallon of automobile fuel and have corn syrup and bacon creatively jammed into every food dish imaginable, I guess God is your logical last refuge. Luckily, He's a forgiving god.

Thankfully, God has gone on the record on this subject. Paul said to the Romans (8:18-21) “For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God; for the creation was subjected to futility, not of its own will but by the will of the one who subjected it.” And a thousand years before, Isaiah (24:4-6) told the Hebrews that “The earth dries up and withers, the world languishes and withers; the heavens languish together with the earth. The earth lies polluted under its inhabitants; for they have transgressed laws, violated the statutes, broken the everlasting covenant.” Other similar quotes abound, but curiously, He is silent about growing Zea mays and Glycine max.

Now I’m not here to proselytize or demonstrate expertise on the Christian or any other bible. I am here, today anyway, to say that it’s way past time for Iowa agriculture to get down on its knees and show some humility and contrition for what has been done and continues to be done to the creation to serve the corporate masters.

In an interesting bit of cancel (agri)culture, the Des Moines Water Works announced a few months ago that they were giving up hope for the Raccoon River after using it as a source supply for the city for the last 74 years. Alternative water sources are being explored. This story barely broke through the noise here in Iowa, even though several national outlets ran with it. The Iowa political and establishment elite were crickets, as they always are, when it comes to these sorts of things.

The plight of the Raccoon River is one of many examples of how the condition of our water is a moral failure of our government to safeguard the public’s property, e.g. our lakes, streams and aquifers. I say to those that want better water and think we can vote our way to it: better say your prayers. The Iowa power structure that maintains the environmental status quo is bipartisan and always has been. Some have recognized this—Bill Stowe, to name one. He tried the courts, and failed, as about everybody knows.

But when you examine these sorts of struggles for justice, which is what this really is, the courts tend to follow, rather than lead, public sentiment. One only need look at the struggle for civil rights in the U.S. south. Court cases only started going the way of oppressed black Americans after protests began in the 1950s. Rosa Parks famously refused to relinquish her bus seat in Alabama in 1955, and the year-long Montgomery bus boycott followed. Only then did a federal court, followed by the Supreme Court, find that the 180 year-old Constitution outlawed bus segregation (1). Numerous other examples of this script played out in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Our water here in Iowa is polluted just as legally as black people were segregated. The agricultural and political establishment have made sure of that. They're so confident in their power that they're not even shy about telling you that. But should that be the standard, legal, or not legal? For an industry and its practitioners who mostly claim to embrace conservative and traditional and moral values, should not the standard be what is just? Call me crazy, but if agriculture had the moral high ground here, they probably wouldn't need "communicators" to force feed us on how righteous they are.

I think sometimes we lean on Aldo Leopold more than we should; quoting him can become almost trite at times. But as I’ve read and re-read his words, it seems to me that Leopold transcends all other environmental writers in that he’s an Orwell-like figure; by that I mean his 80-year-old observations seem like they were articulated only yesterday. It’s interesting and probably not coincidental that his name rarely or never crosses the lips of people in establishment agriculture. He saw early on that what was driving conservation decisions was profit, not environmental outcomes, and certainly not justice (2): “The farmers, in short, have selected those remedial practices which were profitable anyhow, and ignored those which were profitable to the community, but clearly not profitable to themselves.” This so very accurately crystallizes how our industry and elected leaders and agencies think about the environmental condition here in Iowa, i.e., if it doesn’t make economic sense, forget it. This is an injustice to us as citizens that are at the mercy of the polluters.

To circle back to Carl Sandburg, I am convinced the only way we will get clean water here in Iowa is if we fight for it. Some might say it is a utopian fantasy to think we can have clean water here, after a 180 year-long assault on our streams and lakes. But in my estimation, the idea of clean water has moral power.

And ideas with moral power don’t die easily (1).

Zinn, H., 1990. Declarations of Independence Cross-Examining American Ideology.

Leopold, A., 2014. The land ethic. In The ecological design and planning reader (pp. 108-121). Island Press,

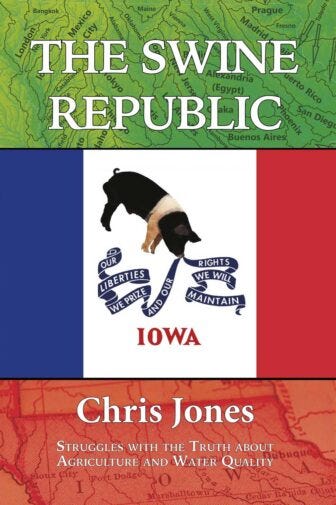

About my book: The Swine Republic is a collection of essays about the intersection of Iowa politics, agriculture and environment, and the struggle for truth about Iowa’s water quality. Longer chapters that examine ‘how we got here’ and ‘the path forward’ bookend the essays. Foreword was beautifully written by Tom Philpott, author of Perilous Bounty. Choice of free book copy or t-shirt for all paid subscribers to this Substack ($30 value).

Just read your opening salvo in your new substack and truer words were never spoken. Have wondered how long it would take the party in power to force your employer to tell you it was time to hit the trail? More than 10 years ago two-thirds of Iowa voters favored a new sales tax fee supporting the environment, but to no avail. Our governor now says "we now have other priorities". We must ask ourselves; why must the ruling party always do what they want when the majority has other ideas? This party bent on voter-suppression also seems intent upon solidifying its rule. We just spent 12 days along the beautiful shores of Lake Erie, where a toxic algae bloom (mostly created by agricultural use of too much fertilizer) recently forced the shutdown of Toledo's water supply. The powers that be are said to be working with local farmers to change their methods and use less fertilizer. I hope they will have more luck than we've had in Iowa. We thank you Chris for your talent as a scientist and being a voice for Iowans who want clean water.

So glad to see you here. Iowa needs your voice.