Please forgive the length of time between this and my last post; I was feeling rotten with Lyme disease for a couple of weeks but I think it was detected and treated early in the game, and I feel pretty well recovered.

The first paragraph of my book, The Swine Republic, reads as such: “People in my line of work attend a lot of meetings. A ballpark guess is fewer than 5% of those meetings generate anything consequential; this book is a result of one those. I came away from that one particular meeting five years ago with the certainty that the Ag establishment here in Iowa had no real interest in cleaning up the state’s water and was mostly operating in bad faith when it came to the issue. On that day, I decided I had to do some things differently if I was going to be able to reconcile my publicly funded job with my conscience.”

I am currently writing the story of that meeting. It will help you understand that story if you know something of the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy and Nutrient Research Center; the essay that follows here is a primer on each. If you feel you’re well informed on that, you may want to wait for part two, which I intend to post in the next day or two.

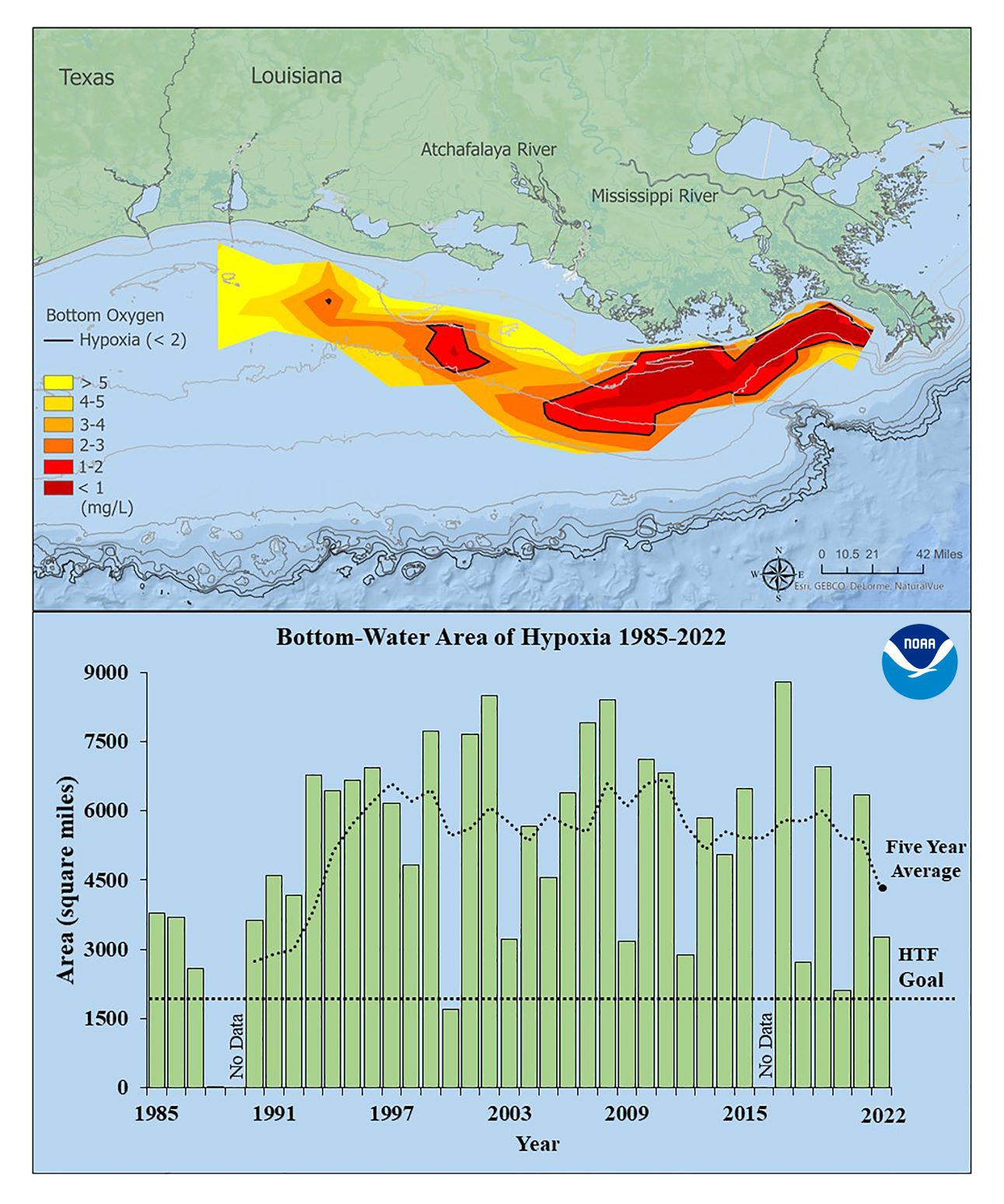

The Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy (INRS) has been the state’s showcase water quality policy for ten years now and was developed ostensibly to address Iowa’s nutrient pollution contribution to the Mississippi River and the receiving Gulf of Mexico. Nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) sourced to cornbelt agriculture travels down the Mississippi and into the Gulf where algae and cyanobacteria (bacteria capable of photosynthesis also known as blue green algae) multiply explosively in response to the easy availability of these nutrients. When these organisms die, their decaying cells consume oxygen in the water column disrupting ecosystem functions and the assemblage of aquatic species. The relative importance of N versus P has been argued, although the consensus now is that N drives this process in saltwater while P is the driver in freshwater, but both nutrients contribute in both systems.

Point sources (end of pipe discharges from cities and industries) do contribute and in the Mississippi basin this has been especially true of P from the Chicago metro, although P discharges have been reduced 92% from the Stickney wastewater treatment plant, the region’s largest.

Iowa has ¼ the human population of Illinois and nutrient contributions from human and industrial wastewater are dwarfed by that from Iowa agriculture, with around 80-85% of P and 90-95% of N sourced to crop and livestock production.

The INRS objectives are aligned with those of the Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Task Force, that being a reduction in the size of the low oxygen zone to 5000 km2 as a 5-year running annual average (5-yr RAA). The initial Task Force target date for hypoxia reduction was 2015; however, lack of success up until that time forced a postponement until 2035. There has still been little or no progress toward this goal, although it must be said that the 5-yr RAA after 2022 is at its lowest level since the 1990s.

It's presumed that N and P levels at the outlet of the Mississippi River must be reduced by approximately 45% to meet the hypoxic areal reduction goals, and this is the stated objective of the INRS and other state nutrient strategies, many of which were modeled after Iowa’s. These strategies were endorsed by the Obama USEPA in the now infamous (Nancy) Stoner memo, and Mississippi River Basin states correctly assumed (thus far, anyway) this endorsement signaled that the federal government would not try to regulate nutrient pollution similarly to what was done in the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

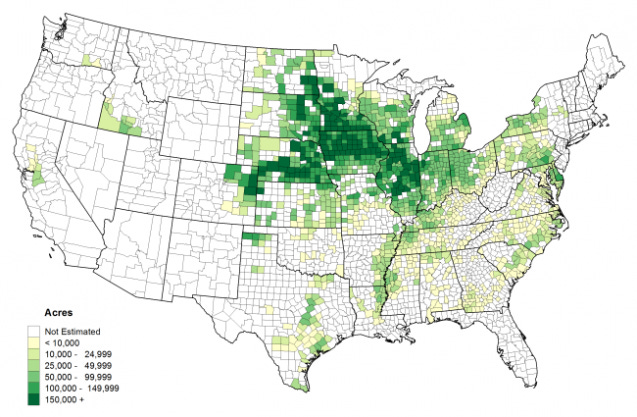

Prior to release of the INRS, a team of scientists was assembled (I was not on it) to conduct a ‘science assessment’ on nutrient pollution and identify farm practices (the INRS also has a point source portion focusing on municipal and industrial wastewater) that could be used by farmers to reduce transport of N and P from their fields. This menu of practices was considered ‘approved’ and eligible for cost share (public) money should that be made available by the State. The strategy, which included the science assessment and a highly controversial policy section put together mostly without input from environmental groups, was released in 2013.

The Iowa Nutrient Research Center (INRC) was subsequently established by the Iowa Board of Regents (BOR) in response to legislation passed by the Iowa Legislature. The center “pursues science-based approaches to areas that include evaluating the performance of current and emerging nutrient management practices and providing recommendations on implementing the practices and developing new practices.” Located at Iowa State University in Ames, the center is funded by revenue received through Iowa Groundwater Protection Act, an amount totaling (until recently) about $1.5 million per year for the INRC. Somewhat ironically, the total funding amount is proportional to tonnage of fertilizer sold in Iowa. This money funded about 60% of my salary at the University of Iowa, two field staff people that operated and maintained the water quality sensor network, 10% of a Systems Analyst position at UI to work on the Iowa Water Quality Information System web platform, several administrative and communications staff people at ISU, and competitive research projects proposed by researchers at the BOR institutions (UI, ISU, UNI).

The competitive research projects focus on improving and developing existing and new practices intended to reduce N and P loss from farmed fields, and on sociological research examining the drivers of practice adoption by farmers. Every year, proposals are submitted by interested researchers and the projects funded on merit as determined by a panel of independent reviewers. These projects provide graduate students the opportunity to study nutrient issues in Iowa and earn advanced degrees doing so, and in the process, hopefully advance the state of the science in this area.

It should be said that the Nutrient Strategy’s basic approach of identifying best management practices (BMPs) and then offering cost share funds from the public coffers to inspire farmer adoption is aligned with the history of farm conservation in the U.S. going back to the Dust Bowl. There’s nothing radical about it other than there is not much evidence that this approach has ever worked (or ever will) for nutrient pollution.

Advocates of the INRS like to say that it indeed has worked to reduce P loss linked to soil erosion from farms (P attaches very tenaciously to soil particles, so reduce soil erosion then reduce P loss). But this claim is dubious on its face and ignores 1) actual water quality data; 2) the role of Conservation Compliance in the 1985 Farm Bill, which required soil conservation plans of farmers; and 3) lack of progress on soil erosion the last 25 years which includes the life of INRS.

A posterior emission may indeed result if a Republican politician asks you to pull his finger, but a more likely outcome is ‘THE NUTRIENT STRATEGY IS WORKING’ will blow out the other end. Either the way, the smell is bad. If they even try to justify the latter, they’ll usually cite BMP adoption data collected by the Agribusiness Association of Iowa. I know, I know, this is sorta like putting Exxon in charge of measuring atmospheric CO2, but such is the integrity of our legislature. They’re able to do this because the INRS was set up to use what is called the Logic Model to assess progress. The Logic Model first focuses on BMP adoption and cultural change on the landscape, a process that may take years or decades (or centuries) before improvements in water quality can be manifested. Your children and grandchildren may move to Colorado or Oregon while you spend your golden years canoeing polluted rivers, but such is life I guess. The Achilles heel of the Logic Model is that it does not quantify things happening on the landscape that make the problem worse: more livestock, more fertilizer and especially for N, more tile. It’s sorta like expecting your waistline to benefit by transforming your IPA indulgence into a Blizzard binge.

Nutrient Strategy detractors like to point out there are no timelines or benchmarks for progress, and no consequences for non-adopters. Of course the latter would require regulation and the Aggies are about as excited with that idea as I am about a prolonged episode of gout. What I think the critics of the INRS often underemphasize, however, is the absurdity of farmer altruism solving the colossal, continental scale problem that is nutrient pollution. There is literally no precedent for a problem of this magnitude being solved through individual actions. None. Nada. Zero.

While the bulk of the INRS governmental effort is concentrated with Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship (IDALS) (i.e. non-point source nutrient pollution), the point source (municipal and industrial wastewater) portion is administered by Iowa DNR. These dischargers are already regulated under the National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES), part of the Clean Water Act. This point source nutrient reduction effort does have a regulatory component with DNR able to leverage reductions from the dischargers through renewal of discharge permits. Back in 2013 when the nutrient strategy was released, I was astonished the regulated point sources (especially the cities) were going along with it. I really couldn’t believe it, to be honest. Accepting a regulatory approach to address the 5-20% of the pollution sourced back to permitted dischargers and a voluntary approach to address the 80-95% of the pollution from the non-point sources was ridiculous and really almost immoral policy in my estimation. When that happened, the cities abdicated what shred of leverage they may have still had over state government and the ag industry when it came to Iowa water pollution. But, as we see 10 years later, Iowa city governments have become reluctant to upset the more conservative state legislature on this and many other issues.

About my book: The Swine Republic is a collection of essays about the intersection of Iowa politics, agriculture and environment, and the struggle for truth about Iowa’s water quality. Longer chapters that examine ‘how we got here’ and ‘the path forward’ bookend the essays. Foreword was beautifully written by Tom Philpott, author of Perilous Bounty. Get a free copy of the book with a paid subscription to this substack ($30 value).

The Iowa Soybean Association is electing board members now. All 17 candidates were asked to name the most important issue facing soybean farmers. No one named water quality, runoff, nutrient loss, or soil erosion. Nearly all of them named profits and markets. Their answers were in the June issue of their magazine Iowa Soybean Review.

The last paragraph is compelling. When the INRS was being developed, were point source folks at the table? I was under the assumption that they were forced to comply, and they didn’t really have a choice not to accept the conditions (regulations for them, and a voluntary approach for non-point sources of pollution), but maybe my assumption is incorrect?