The catastrophic release of nitrogen fertilizer into Western Iowa’s East Nishnabotna River continues to make the news here in Iowa and now nationally. Iowa DNR is now saying it likely resulted in a top-5 fish kill for the state, which, considering this is Iowa, means file it under “E” for Epic. To review: about 3 million pounds (265,000 gallons) of liquid fertilizer was released on March 9-10 from the New Cooperative facility in Red Oak into the East Nishnabotna River, essentially sterilizing the 60 miles of stream between Red Oak and the Missouri River near Watson, MO. It’s safe to say everything in that river is dead unless space aliens surreptitiously stocked extraterrestrial species adapted to unearthly conditions when nobody was looking.

Iowa DNR is estimating 750,000 fish were killed by the release, with the most valuable of those being 7700 channel catfish, a species targeted by sport fisherman. (Note: 7700 channel cats in 60 miles is not a lot for an Iowa stream. A clean stream may have 5000 pounds per mile.) According to DNR protocols, those would have an economic value of $115,000 with the other species, mainly rough fish, minnows and invasive species, totaling $85,000.

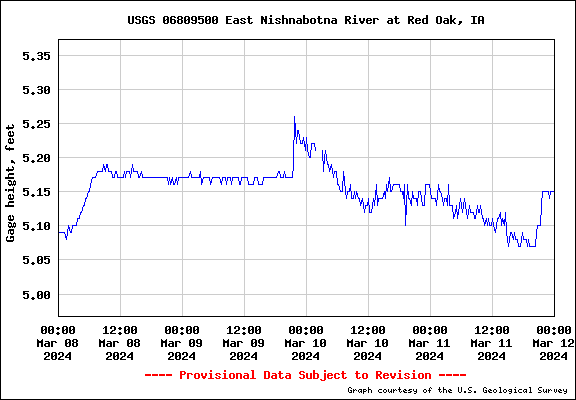

I posted a piece about this last week on my substack feed but thought this story merited a little more poking around. It just so happens that the U.S. Geological Survey has a stream gage measuring water elevation and discharge in the river about 2000’ downstream from the New Cooperative operation. I looked at the data for that site, and the gage clearly detects an increase in flow occurring at 9:30 pm on Saturday, March 9, with flow returning to the pre-spike level about 5:45 a.m. on Sunday morning (see graph below).

Measurements at the gage are recorded every 15 minutes. From those measurements I estimated the “extra” flow associated with the fertilizer release, based on the baseline flow prior to 9:30 pm on 3/9. That extra flow amounts to 1.3 million gallons, which seems implausible since the tank holding the material apparently has a 500,000-gallon capacity and the reported volume of the release is 265,000 gallons. I can only think that since the gage is so close to New Cooperative that there was a localized flow effect from the release that disproportionately affected the gage relative to the river as a whole, something made more likely by the very low flow of the river. Nonetheless, the USGS gage does pinpoint the time of the release.

If the release was indeed 265,000 gallons, the fact that it occurred over 8.25 hours indicates the fertilizer product was gushing out at 32,121 gallons per hour, about 535 gallons per minute. In my last post, I had it estimated at 5000 gallons per hour (83 gallons/min) assuming a 48-hour release. For reference, my kitchen tap in Iowa City flows at about 1 gallon per minute.

It's also been reported that the material was 32% nitrogen. That means the release contained 960,000 pounds of that nutrient. This likely exceeds the entire load transported by that river in some years, that coming mainly from about 1000 square miles of cropped fields.

In some ways I feel sorry for the poor guy that left the valve open. Things like this CAN be prevented if the bosses are serious about preventing them. It’s not beyond our engineering know-how to detect potentially catastrophic leaks from storage tanks, whether they’re caused by human error or mechanical failure.

But, Iowa agriculture is all about squeezing every last dime out of Iowa’s landscape, and most certainly not about protecting the environment.

This is a good time I think to talk about Western Iowa rivers. Although no part of Iowa has been left undisturbed by Genghis Khorn and his horde of pillagers and plunderers, their cruelty on Western Iowa’s environment may be unmatched anywhere else in the country. Apart from the upper reaches of the Little Sioux, the rivers have been trashed beyond what pre-1930 residents would recognize. One of my colleagues once said that the only thing that would bring these rivers back is another Ice Age, and I tend to believe that.

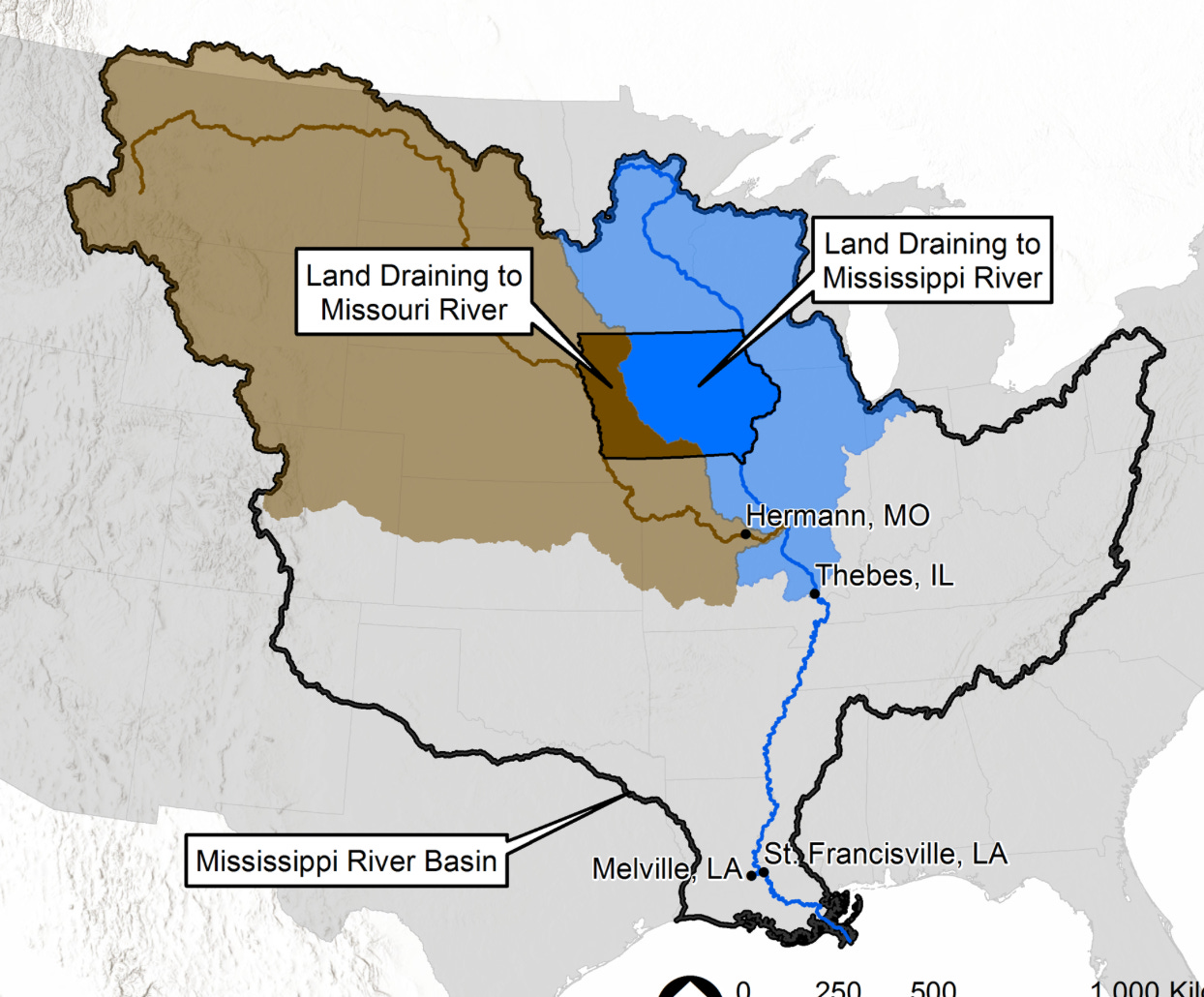

I should qualify what I mean by “Western” Iowa; in this circumstance, it’s everything that ultimately drains to the Missouri River, about 31% of Iowa’s area.

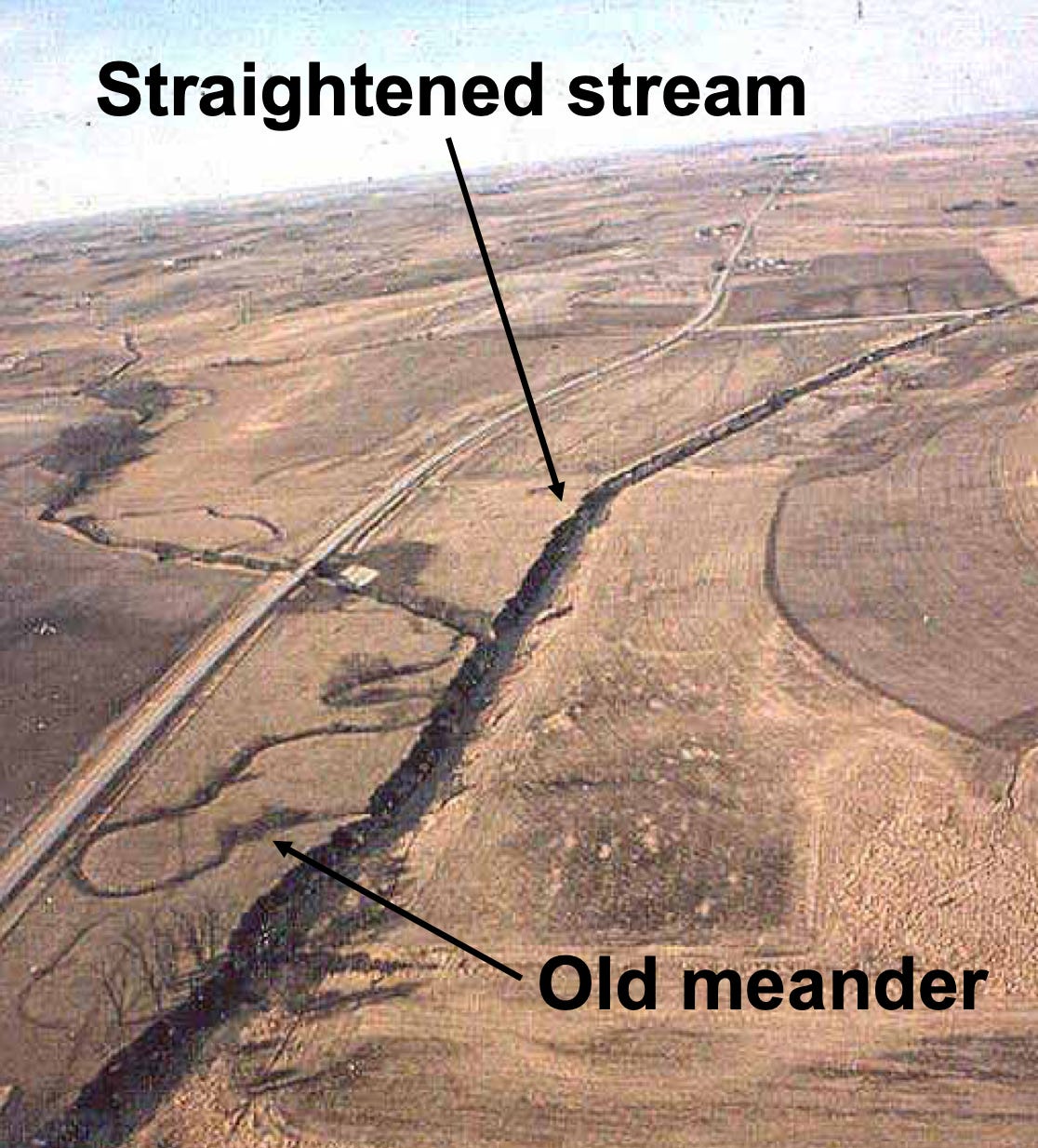

While the original sin of Western Iowa agriculture may have been leaving none of the prairie unturned, the real abomination was straightening rivers so fields could be squared up for easier farming. The streams were straightened using dynamite and steam shovels and the spoils often were used to levee off the river, so it wouldn’t flood the adjacent cropped field. Reducing the length of a stream stretch by meander removal causes it to go faster. Prior to straightening, the meandering prairie streams were slow moving, clear water systems that supported a diversity of clean water species.

All water is what we call “sediment hungry” in varying degrees controlled by slope and other physical factors. The hunger in these straightened and sped-up streams, cut off from their meandering ways, was sated on the stream bottom. Since Western Iowa is covered with easily erodible and deep loess (windblown) soil, sometimes hundreds of feet thick, the streams were able to cut downward a long way to form virtual canyons, a process that continues in the present.

A straightened river stretch degrades the stream both down- and upstream. As the stream channel vertically erodes downward, the erosion migrates upstream forming a “headcut” that won’t stop until unerodable material (such as bedrock) is reached. High flows rushing downstream from a straightened stretch to a still-meandered stretch can overwhelm the meandered channel, causing flooding and streambank erosion that otherwise might not have occurred. Thus, stream straightening is an addictive drug, once you start, you can’t stop until the river has been beaten into submission.

The downcutting streams imperiled countless bridges in Western Iowa by exposing the pilings. This was a desperate situation for a time, and the taxpayer-funded Hungry Canyon Alliance was formed to try to stabilize the malignant hydrology caused by agriculture. This was done through rip rapping banks and several other strategies.

In some cases, a low-head dam was constructed upstream of the bridge to slow the water (making it less sediment hungry) before it traveled under the bridge. In farm country, manure solids and other muck accumulates behind these dams, making them vile cauldrons of disgusting filth. In some cases, E. coli survive for long periods and may even multiply in this environment and are seeded to the rest of the river during high flow events that scour out the pool, one likely reason why some streams are chronically impaired with these bacteria.

Few of our native species evolved such that they can endure this disturbed hydrologic condition. Farming up to the brink of streams, continued soil erosion, and chronic nutrient and pesticide pollution have exterminated all but the most pollution tolerant species. Most sight feeders are gone, leaving rough fish and invasive species like carp. One species popular with many Iowa anglers, the channel catfish, endures because it can capture its prey without the benefit of sight.

About the best we can say about these Western Iowa sewers I mean rivers is that none have caught on fire—at least not yet. I challenge you to find any place in this country that has mistreated its water resources worse than Western Iowa. Any. Place.

Nobody but nobody should think this New Cooperative incident was a one-off event. It’s very much part and parcel of how agriculture has treated Iowa rivers since at least 1930 and maybe before. People, including me, have been speculating about how Iowa DNR will almost certainly treat the operation with kid gloves. Let’s face facts here—the quest to completely annihilate Iowa’s natural environment is something ingrained in our culture and our collective psyche, and this includes our government agencies.

There is scholarly literature that has examined this callous mentality.

Economist Elinor Ostrom was awarded the Noble Prize in economics for her work analyzing economic governance of the commons. In this context, ‘the commons’ are the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including things like lakes and streams that are not owned privately and (presumably) managed for both individual and collective benefit. In a 1999 paper, Ostrom stated that “For users (of the resource) to see major benefits, resource conditions must not have deteriorated to such an extent that the resource is useless, nor can the resource be so little used that few advantages result from organizing.” That in a nutshell describes Iowa in general and especially Western Iowa. Many of us accept the degraded condition because we don’t know any better. Those glancing down from a bridge at the Nishnbotna or the Boyer or the Soldier Rivers may think what they see is the ‘natural’ condition, something known as a landscape bias. And those of us that do recognize the degradation for what it is see little hope of reversing it. Thus, we’re stuck in this never-ending cycle where streams are killed, and the killers get off either scot-free or with a hand slap.

I wish I could hope that the New Cooperative incident might be a wakeup call for Iowans regarding the condition of their natural resources and the true character of the industry that has plundered them, and that has every intention of continuing this plunder. But I’d be lying if I said I was hopeful. The plunderers fight tenaciously to maintain their pollution privileges, and so very few within our institutions have the courage to meet them head on. So very few.

That’s why I think it’s time for Iowans that still value nature to circle the wagons. Some parts of the state are so degraded and so hopeless that as a practical matter, they need to be written off until after the next Ice Age. This includes everything flowing to the Missouri River. We need to protect the last island of environmental integrity that we have, which is far northeast Iowa—Allamakee County, the eastern half of Winneshiek County, the northeastern half of Clayton County, and parts of Dubuque and Jackson Counties. Some streams outside of this area, notably the upper reaches of the Wapsipinicon and the Cedar Rivers, and maybe the Boone and Maquoketa Rivers, are probably salvageable but only if we organize and meet agriculture’s tenacity head on.

I’m a member of the Iowa Writers Collaborative. There are some great writers (shown in the list below) and some big names in that group. They’re all posting here because like me, they want Iowa to be a better place to live, and words are our tools.

In keeping with the season, Chris is the John the Baptist, the "Voice in the Wilderness" witness and scribe detailing the environmental suicide of Iowa. I don't know what it will take for the 95% of Iowa's population that are NOT farmers, to demand the same restraints on the "Factories without walls" that are enforced on the lowliest tire and muffler shop , or machine shop. Maybe when communities are paying $100K a day instead of $10K to remove nitrates? When the cancer rate becomes so high that even the rapture-addled yahoos that populate much of the state cannot deny the connection? Maybe Ivermectin will work on cancer too!

And taxpayers are paying for the privilege of have the countries largest open sewer system. According to EWG.ORG, who collects such data, Iowa was NUMBER ONE in commodity subsidies from 1995 to 2021, totaling nearly $25.5 BILLION dollars. And by congressional district , guess which one dominates in suckling at the government teat? Good old independent-don't-tread-on-me-no-socialism-Gods-Guns-n-Grift 4th District. Ya can't make this stuff up.

Good piece!! Sad to know all this. We’re going to need extraordinary people to change these ordinary people’s relentless effort to keep ruining our state. Like Einstein said: “You cannot solve a problem with the same mind that created it.”