Note: much of the material for this essay can be sourced to the book The River We Have Wrought, A History of the Upper Mississippi, by John Anfinson. I came to this book quite by chance browsing the rare bookstore in McGregor, Iowa. It was published in 2003 and this particular copy was wrapped in clear plastic of some sort and a note by it on the shelf said “Inquire at register if you are interested in this book.” I took the book up to the counter and the owner unwrapped it; I thumbed through a few pages and said I would take it. The owner seemed hesitant to let it go, but I’m glad she did. If they ever get the road fixed through downtown McGregor, you should check out this store.

I saw the Upper Mississippi River countless times during the 16 years I lived in the Twin Cities and fished the stretch from Red Wing, Minnesota down to Alma, Wisconsin on days too numerous to remember. The area around Red Wing was one of my favorite places to fish and at times the fishing was so good I wondered why so many Minnesotans went to Canada to catch walleye. Fishing was always best in cold weather when baitfish were attracted to the warm water discharged by the Prairie Island Nuclear Plant, which used the river for cooling water. Minnesota’s other nuclear power plant is also on the Mississippi at Monticello, illustrative of the heavy industrial use the river receives.

Those days of great fishing required what I now consider to be an almost heroic tolerance to cold. Launching your old red Lund into the 40o river and traveling upstream full bore for four miles into a driving snowstorm is not for everybody, and two hours was about the limit for me under those circumstances. The luxurious boats so many have these days enable anglers to stay warm and fish all day even in the coldest weather, something I suspect has diminished the fishing.

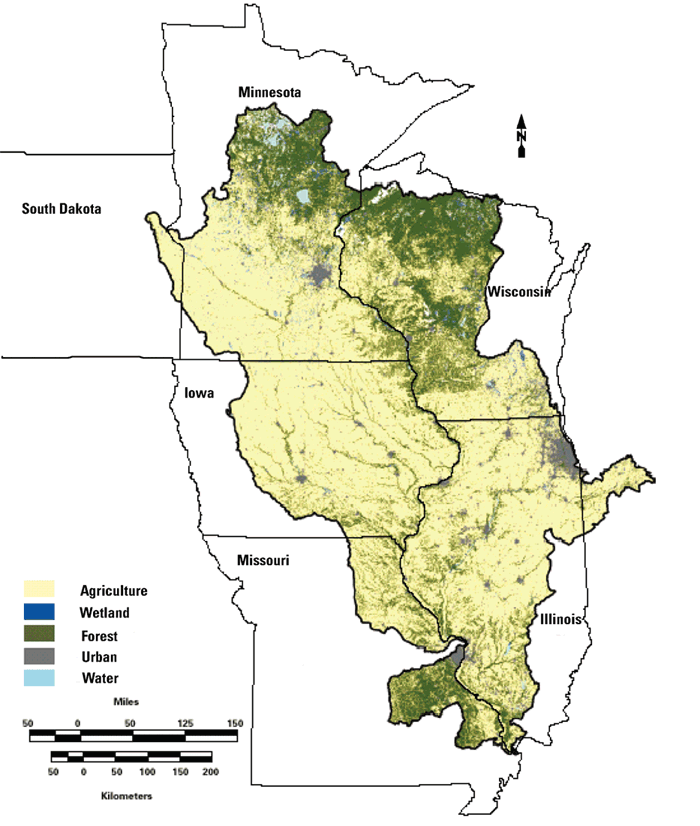

The boundaries of the Upper Mississippi River include all streams flowing to the Mississippi stretch above its confluence with the Ohio River, not including streams flowing to the Missouri River. In some circumstances, the watershed above Minneapolis is distinguished as the ‘Mississippi Headwaters’ but for my purposes here I include it as part of the ‘Upper’. The watershed area totals just shy of 190,000 square miles (slightly bigger than California) and claims parts of eight states: South Dakota, Michigan, Indiana, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Iowa and Missouri, although the bulk of the area is in the last five and they are generally considered to be the Upper basin states.

Having seen many rivers across the U.S., I think it would be hard to make the case that the Upper Miss is our most beautiful river. But even a few hours spent anywhere on the stretch from Red Wing down to Bellevue, IA can make you forget the Yellowstone, Colorado, and others whose backdrops benefit from vast, unpopulated and undisturbed vistas. The Upper Miss flows through and receives water from huge metropolitan areas and bisects one of the most altered landscapes on earth—the U.S. Cornbelt—which to me multiplies the beauty of the river and the surrounding scenery such that they seem misplaced.

The Mississippi’s biological and hydrological integrity has suffered from the onslaught of civilization and modern agriculture for two centuries. Midwestern cities have used the river as a sewer and no urban wastewater treatment plants existed until 1938 when the Twin Cities’ plant was constructed. It was once common practice for St. Paul to dump its garbage onto the Mississippi’s winter ice, and Minneapolis dumped 500 tons of garbage into the river every year during the 1880s. Garbage, raw sewage, and dust from sawmills dumped into the river made some stretches unsuitable for even the most pollution tolerant species.

Navigation interests have craved the river for their own since the earliest days of white settlement. The great white pine forests of Minnesota and Wisconsin were felled and the logs floated down the river to sawmills as far south as Missouri. Clinton, Iowa was once known as the ‘Lumber Capital of the World’ because so many logs were milled there. The erosion resulting from deforestation and agriculture took a huge toll on the river’s water quality almost from the beginning.

The trees eventually ran out and other shipping interests clamored for ‘improvements’ to the river’s channel that would accommodate larger craft. Especially treacherous for large boats were the 11 miles upstream of Keokuk, Iowa, known as the Des Moines rapids; the Rock Island rapids near that city; and several stretches between St. Paul and LaCrosse, Wisconsin. Navigation proponents around the turn of the last century saw alteration of the river as part of the prevailing ‘Manifest Destiny’ mindset of the country. Prominent geologist and Farley, Iowa native W.J. McGhee crystalized this attitude by saying “The end is the manifest destiny of North America. For not until seagoing craft can enter our great commercial artery, so nearly perfected by Nature (emphasis mine), ply thence to all ports, and carry our products direct to the ends of the world—not until then will America come in to its own.”1

Agricultural interests were especially keen to deepen the channel for large boats for two reasons: 1) over-production in Midwestern agriculture was a problem even in the early 1900s, and farmers wanted access to foreign markets; and 2) the railroad barons held a monopoly on grain transport and many thought that river shipping would create competition.

Early efforts to channelize the river mostly focused on wing dams that channelized flow to make the river ‘naturally’ dredge itself, and closing dams that reduced flows into side channels. First a 4.5’-deep channel and then a 6’ channel were the objectives but it was eventually concluded that a series of dams accompanied by locks for boat transfer that would maintain a 9’ deep channel was the most desirable option. By the 1920s, the 9’ idea had momentum and conservationists worried that the altered hydrology and pooling of polluted water would create a slow-moving cesspool uninhabitable by native species, including migrating birds using the river as a flyway. But the surveying for the project moved forward and Congress ultimately funded construction in a series of bills after the election of FDR. The last of the 23 funded lock and dam sites was finished in 1940 at Clarksville, Missouri and thus the great Upper Mississippi has been a controlled river since then.

There were conservation defeats and victories associated with the harnessing of the Mississippi for shipping. One of the victories was the preservation of the wetland areas in the 30-mile stretch centered around Lansing, Iowa, known as the Winneshiek bottoms. Agricultural interests were keen to drain the floodplain and claim it for farming, but conservation groups, including the Izaak Walton league, were able to persuade Congress to pass a bill authorizing land purchases between Rock Island and Wabasha, MN, creating the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife Refuge. President Coolidge signed the bill in 1924.

Although the 9’ channel project would later inundate some of the refuge, the creation of the refuge would have a lasting legacy: it protected the floodplain from farming. Above Rock Island, most of the floodplain is still connected to the river and only 3% of it is farmed.2 Between Rock Island and St. Louis, 53% of the floodplain is farmed. Thus, although the upper river is clearly ‘disturbed’ in the ecological sense by the altered hydrology created by the dams and inundation of lowland wetlands, the stunning panoramic views of the bluffland and valley remain unadulterated by corn and soybean fields and create the appearance of a pre-white-settlement relic.

Although the ‘moving cesspool’ feared by conservationists never materialized thanks to wastewater treatment plant construction along the river, water quality in the Upper Miss is very degraded. The upper river can send south nearly 1.5 billion pounds of nitrogen from row crop and animal agriculture in average year.3 About 69% of Iowa drains to the Upper Mississippi (the rest draining to the Missouri River), an area of land that’s about 21% of the total Upper Mississippi drainage area. The 21% that is Iowa delivers 45% of the river’s nitrogen in a typical year.3 To my observation, the quality of the river water really starts to noticeably decline south of Dubuque; I’m told by Southern Illinois University river researcher Jon Remo that he thinks there is another step decline in water quality below the Iowa River confluence in southeast Iowa.

About any water pollutant you can think of is present at some level in the Upper Mississippi—heavy metals, E. coli, PCBs, pesticides, and maybe most importantly, the emerging contaminants in the PFAS family. That all being said, if the Upper Mississippi were an Iowa interior warm water stream, it would be our very best in terms of overall water quality, and this by a long shot.

Even with all the hydrological and water quality disturbance, the river remains one of the most biologically diverse freshwater systems on earth, this helped by its north-to-south character which enables species from a wide range of latitudes to migrate back and forth; however, the lock and dam system has restricted this movement for many or most of these species. Unfortunately, invasive species like the Asian carp have been able to migrate up the river and threaten native species assemblages. Well over 100 fish species are native to the river and 25 are sought by anglers—an amazing number for anybody that enjoys the sport.

Can the river’s current degraded but somewhat acceptable condition endure future stressors? Extremes of flow associated with climate change and the desire for larger tow/barge capacity have some in the barging industry howling for navigation improvements. Corn and soybeans comprise most of the modern cargo and agricultural interests wield great power at both the state and federal levels of government. Pollutants like PFAS threaten the viability of both commercial and sport fishing for human consumption, and invasive fish species have taken over some sub-watersheds like the Illinois River. Nutrient (nitrogen and phosphorus) pollution degrades the river for aquatic life, recreation, and municipal water supply. It’s hard to see the river maintaining status quo without robust intervention by state and federal government.

1) W.J. McGhee, “Our Great River,” Worlds Work, Feb. 13, 1907, 8576.

2) Cumulative Effects Study, Draft, 92, 109-110, 120. McGuinness, “A River”, 19.

3) Jones, C.S., Nielsen, J.K., Schilling, K.E. and Weber, L.J., 2018. Iowa stream nitrate and the Gulf of Mexico. PloS one, 13(4), p.e0195930.

About my book: The Swine Republic is a collection of essays about the intersection of Iowa politics, agriculture and environment, and the struggle for truth about Iowa’s water quality. Longer chapters that examine ‘how we got here’ and ‘the path forward’ bookend the essays. Foreword was beautifully written by Tom Philpott, author of Perilous Bounty. Get a free copy of the book with a paid subscription to this substack ($30 value).

Fascinating. BTW, the opening paean to the book by Anfinson can be personally explored. On Amazon.com--one new copy and 11 used are available as is the Kindle version.

Thanks for a readable and comprehensive summary!