Well, drained.

Finally, the end of a sad chapter for Iowa agriculture

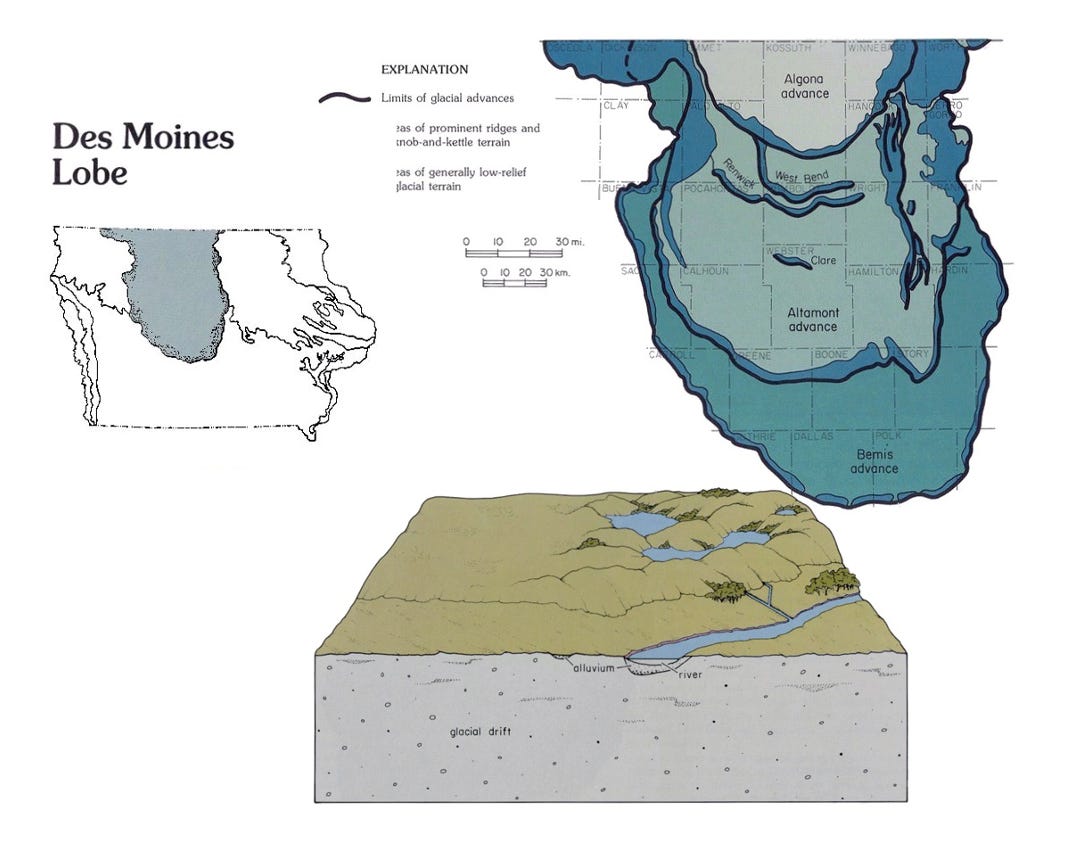

Pretty much all of Iowa has lain beneath glaciers at one time or another, even the so-called Driftless Area where many mistakenly assume glaciers never tread. The most recent glacier to enter Iowa, this during what geologists call the Wisconsin period, melted only about 11,000 years ago. This was only 2000 years before Homo sapiens started growing corn and just 6000 years before we learned how to communicate with writing.

The Wisconsin glacier intruded into North Central Iowa and didn’t stop until it reached the present location of the Iowa state capitol building. Roughly 500,000 years separate the landscape architecture south of Des Moines’ Fleur Drive Bridge from that on the north side; Glacier Contracting LLC handled both jobs. The fist-sized rubble pushed by the leading edge of the Wisconsin glacier, now buried under 30 feet of sand and silt, makes shallow groundwater especially easy for Des Moines Water Works to extract from the Raccoon valley. That ease of extraction is further enabled by the aquifer’s hydrologic connectivity to the river and along with that, most of the river’s pollution, especially nitrate.

The area of Iowa covered by the Wisconsin glacier is now called the Des Moines Lobe. There’s some thought that the Des Moines Lobe ice and that of the similar James River Lobe to the west were the result of water melted beneath and as a result of the enormous glacial ice pressure to north. That melt water then refroze as it flowed south. Essentially these lobes of ice were squeezed out from beneath the main body of the ice cap.

The Des Moines Lobe would look quite different from the rest of Iowa were it not all covered with only two species of plants. The Lobe is not flat, like the Red River of North valley and much of central and central Illinois is flat. It is, however, approximately level, meaning that overall relief (i.e. slope) from one end to the other is small. Imagine a tabletop scattered with overturned saucers and silverware—that’s the lobe—not flat but level. Much of the space between the saucers was filled with ponded water—the pothole wetland ecosystem.

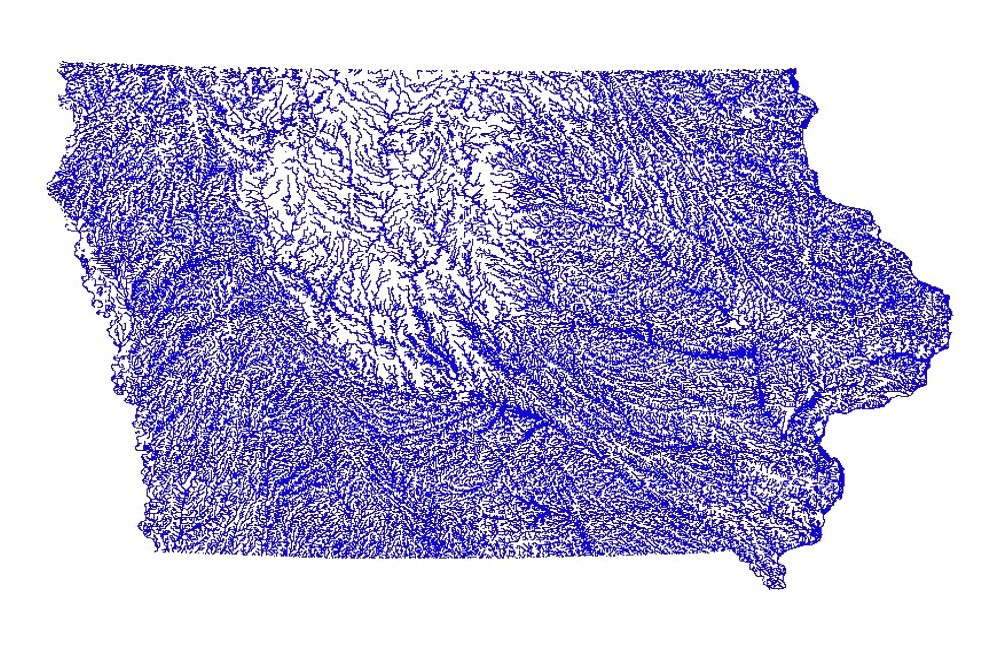

The 11,000 years since meltdown is but a blink of an eye for nature, and especially in terms of stream development. Stream density, i.e. overall stream length per unit area, is low on the Lobe. There just hasn’t been enough time for many streams to form. Much of the area was what we call ‘internally drained’, i.e., water came in via rain but the only way out was down, through seepage to aquifers, or up, through evapotranspiration.

When Europeans arrived in the mid-1800s, large swaths of the Lobe were uninhabitable for human beings. Ever wonder why Iowa has 99 counties and not 100? Well, 100 it would have been but the area designated as Bancroft County in North Central Iowa was so unhabitable the legislature just gave it to Kossuth County, doubling its size.

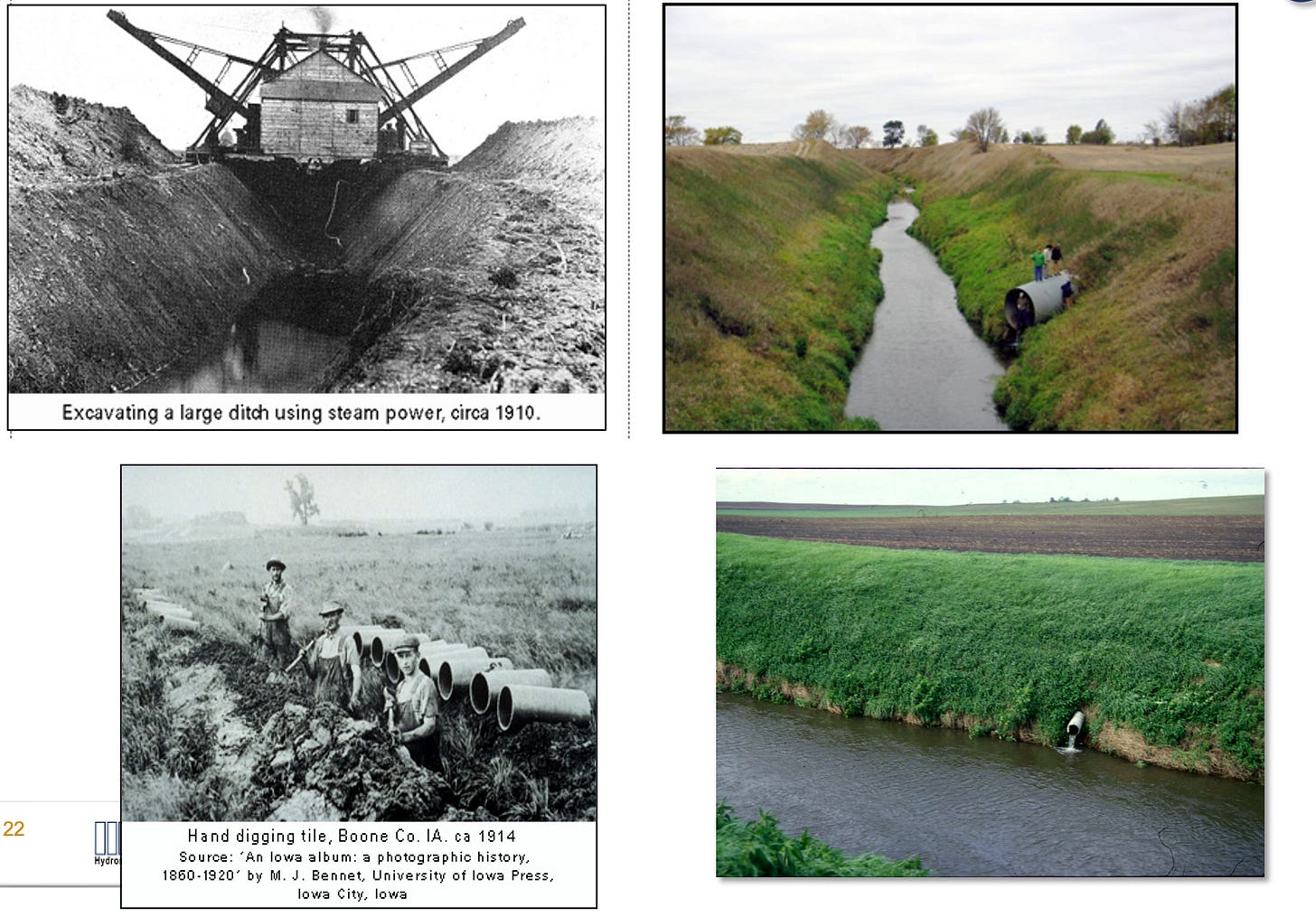

As the drier parts of Iowa filled up quickly with aspiring farmers, late comers were faced with making do with the remaining swampy land or moving on, if they could. Drainage of ag land in Europe had been happening since Medieval times and it seems likely that those drainage masters the Dutch took one look at the Lobe and said ‘geen probleem.’

What Mother Nature couldn’t do in 11,000 years, e.g. form streams, newly arrived white people did in a few decades. Steam shovels dug trapezoidal ditches to connect upland areas to the sparse stream network that did exist, namely the North Raccoon, Des Moines, South Skunk, and the upper reaches of the Iowa and Cedar Rivers. Clay field tiles (pipes that collected subsurface water) were installed four feet down, lowering the water table and depriving the potholes of the water which was now discharged into the constructed ditches. The Lobe was sucked dry from below and an entire wetland ecosystem went quietly into the night over the course of a century (1850-1950).

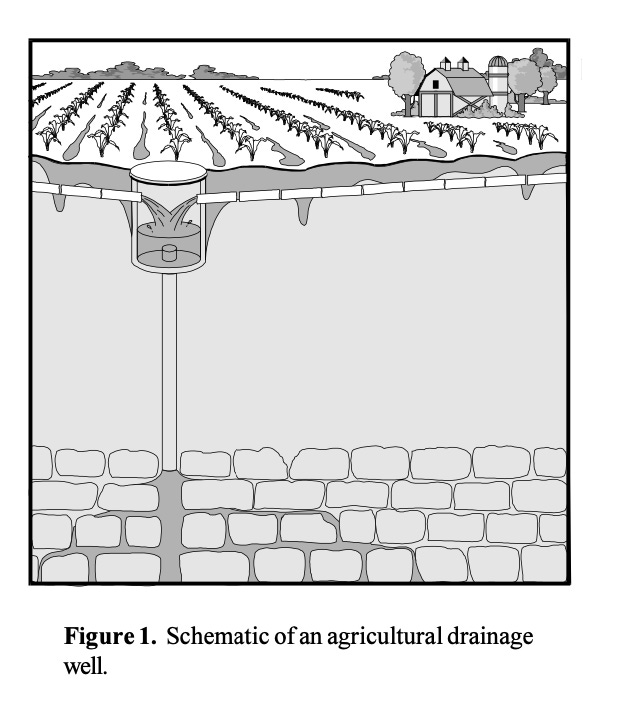

Annoyingly for many, some of these field tiles couldn’t be conveniently connected to a constructed ditch or a stream. If your field lies within a large internally drained area, then your drainage water needs to climb (or get pumped) over some hills to get out. Or, more practically, your outlet pipe needs to be buried deep enough under the glacial garbage ringing the pothole such that the water can flow out by gravity. This was too expensive for many. Undaunted, somebody somewhere, probably on a Friday night in an early Humboldt or Algona or Pocahontas tavern, or some other place where crazy ideas were hatched, said “hey, let’s pipe it down 250 feet!”

Wells were drilled and cased through the glacial ‘drift’ down to the porous limestone bedrock. Field tiles were connected to the well casing near the surface using a caisson, cistern or pillbox of some kind and this nuisance tile water was entombed in the Lobe’s aquifers. Water seeping down through the bottom of a wetland might take centuries to reach a bedrock aquifer; we shortened that process to mere seconds. How many of these things were built is anybody’s guess, but most estimates range between 300 and 700.

A rational person might read these words and think it’s intuitively sub optimal to put ag drainage tile water into aquifers that you might also drink from. Yeeeeaaaaah.

But you also gotta remember that even today, many from farm country fondly remember drinking cold water from a back forty field tile on a scorching hot day spent baling hay or some such thing. Around 1980, people aware of this practice started to think, yeah, not good because tile water contains pesticides and sky-high nitrate, and they started thinking these things should be capped. It’s probably a near certainty that a fair number of cancer deaths and miscarriages resulted from the practice, but let’s not talk about that. In a statement that reflected a different era for Iowa DNR, their staff wrote in a 1999 research document that “Outside of the areas influenced by ADWs (ag drainage wells), very few people were aware of the threat to groundwater contamination posed by ADWs.”

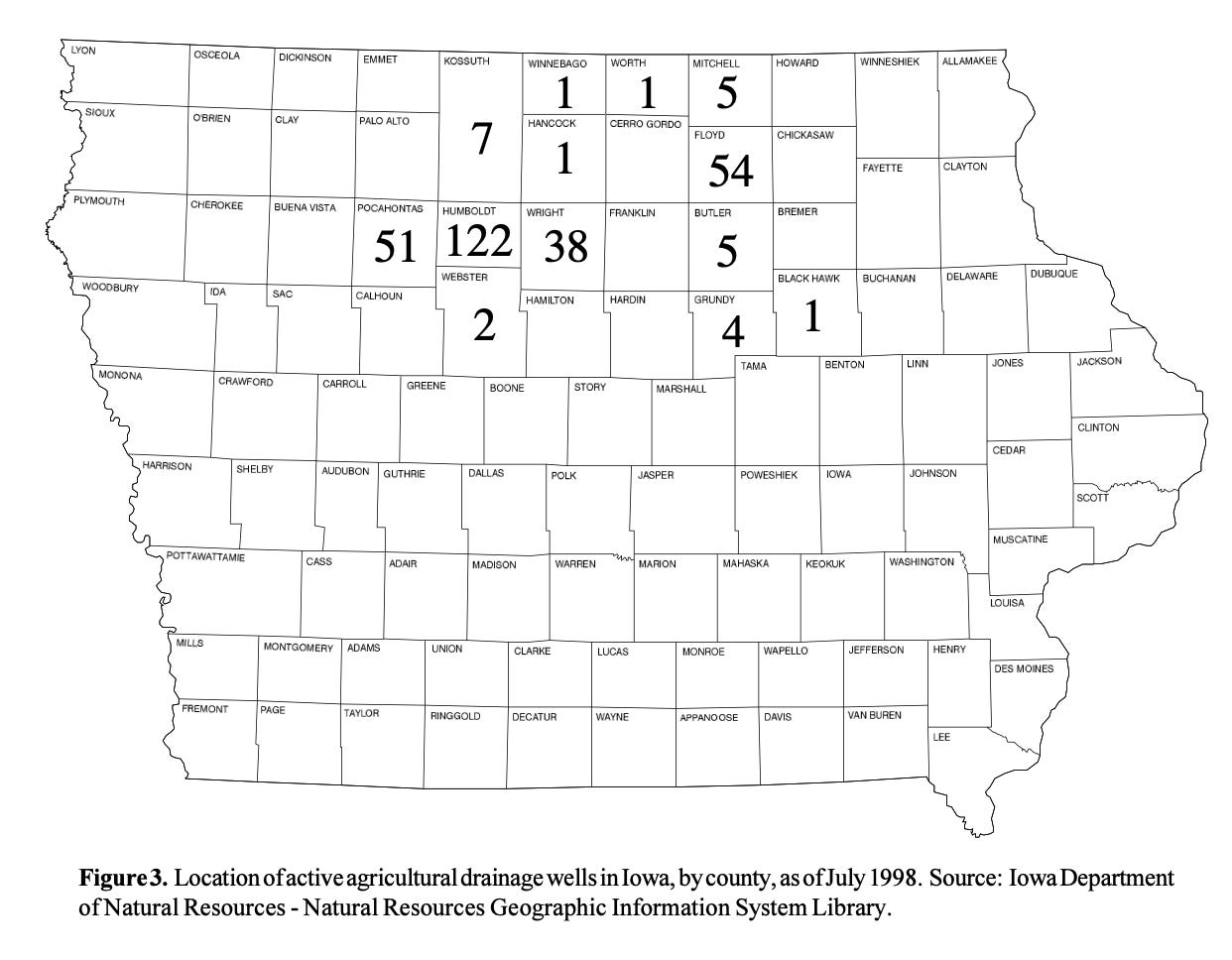

In 1987 the Iowa Legislature enacted the Iowa Groundwater Protection Act (try to imagine that happening today—you can’t), requiring study of the ADWs. Iowa Department of Land Stewardship (IDALS) logged an inventory of about 300 that could be found. About 1/3 of those were closed by the landowner or with funding from the Watershed Improvement Review Board (now defunct as far as I know) or were determined to be non-functioning. This left 195 ADWs to be mitigated. Iowa DNR began monitoring and permitting the remaining ADWs until they could be closed.

In 1997 the legislature created a fund to cover costs for closing the remaining wells; about $25 million in taxpayer money was ultimately used to close the last 195, along with about $12 million in funds from other sources including landowners. Last month IDALS secretary Mike Naig announced that the program was complete—all remaining known wells had been closed.

While the time taken (45 years) between realizing there was a public health risk and closure of the last well is unconscionable in my view, it is good that these things have been closed and it’s fair that public money was part of the solution, as the decision to install them was made by people that must surely all be dead by now. Perhaps some of them died as a result of drinking the pollution they generated—who knows. I think it’s likely the pace and quietude of the task was deliberate. After all, if you admit that tile water dumped into rural wells is dangerous, where does that leave you with downstream cities like Des Moines whose municipal supply is sourced back to the tile-dominated Raccoon and Des Moines Rivers? Makes me wonder if the attorneys in the dismissed Des Moines Water Works lawsuit ever considered this.

Of course, the tiles draining into these wells didn’t just sink into oblivion following well closure, they’re still out there but now instead of discharging into the rurals’ aquifers, they now discharge to the Des Moines Lobe stream network, which of course supplies the municipal drinking water not only for Des Moines and suburbs, but also Cedar Rapids, Ottumwa, and Iowa City. Apparently, a handful (7) of the final mitigated outlets drain to a constructed wetland first, at least quenching a portion of the nitrate. So, I guess take comfort in the fact that it only took 40 years for someone in government to see the hypocrisy here.

Source Material

Iowa Agribusiness Radio Network, November 19, 2024. Secretary Naig celebrates the closing of Iowa’s last remaining ag drainage wells.

Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship. Ag Drainage Well Closure Assistance Program.

Seigley, L S; Quade, D J; Skopec, M P. Groundwater quality response to closure of agricultural drainage wells in Floyd County, Iowa. Iowa Geological Survey Bureau Technical Information Series 40. July, 1999.

Day, S., 2014. Assessing the style of advance and retreat of the Des Moines Lobe using LiDAR topographic data.

Have you explored the variety of writers, plus Letters from Iowans, in the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative? Members are shown below.

Fantastic article, adding to my growing list of ASIDK(Amazing Stuff I Didn't Know). The Swine Republic is a wonderful science journal , especially for the science challenged like myself, best money I spend all year.

Outside of military service, I have been in Iowa all my nearly 70 years, and for decades looked askance at places like New Jersey, New York, Louisiana, Oklahoma and other states where the chemical or oil industry dominated state legislatures or outright mobsters( but I repeat myself) just did what they wished and what was most financially expedient with hazardous waste. Having relatives in Philadelphia, I would occasionally read headlines like "Philly Mob Boss involved in Jersey illegal waste disposal racket" , and think us of the bib overall yeoman-of-the-soil types superior. Bullshit. The Mob was simply more upfront about what they were doing, and not hide behind the pretense of caring for soil and water like the Iowa Legislature does. But the Mob was less efficient in they had to pay the expense of dumping waste in dark-of-night operations, bribes, etc. If they were truly on top of the game , you get taxpayers to fund it!

After the soil is depleted in 50 years or less, and no amount of injected or otherwise applied nutrient will revive it, after we have to import drinking water to lower our exploding cancer rate, maybe, just MAYBE Iowa will rein in the Corn/CAFO Mafia. Until then "Fuggedaboutit"

Things one learns despite realizing ignorance was bliss. Thank you, Chris. Now I am wondering how to cleanse the Xenia Rural water in my faucets or just learn from the past and only drink fermented or distilled beverages