I’ve planted and harvested a ‘big’ vegetable garden for about 20 years now, except for a couple of years when circumstances forced sanity to prevail. How big is big when it comes to a vegetable garden, you ask? A quick internet search will plant it in the 200 ft2 per person territory, so, 800 ft2 for a family of four, give or take. Double that if you want to include space-eating crops like melons and winter squash. And that’s the just eating part of the equation; the part that requires bending over or being at the wooden handle end of a tool of some sort requires a whole separate algorithm.

Ok, I’ll admit it. My gardens haven’t been big. They’ve been stupid big, which is like big on edibles, and by that I don’t mean the garden variety of edibles. Saying my gardens are big is like saying a Hummer is big. Sure, a Hummer is indeed ‘big’, but it’s in a big category that requires a two-word descriptor. Maybe call my garden a BFG (attn: Jon Green). My gardens have made me look unhinged at times, which might explain some things, come to think of it. I think my stupidest biggest effort was about 40’ x 100’ for five people, so that’s 4000 ft2, which is 800 ft2 per person and a size the internet says is adequate for four families of four. 42 big. To my state of mind’s credit, that garden did include space eaters like melons, potatoes and sweet corn and vegetable eaters like whitetail deer which hung around the outskirts like Boone and Crocket infamy was on their bucket list. So I was knowingly writing off a bunch of it to the deer from the get-go. Even so, the local food shelf had a forklift operator on speed dial and summoned him immediately upon seeing my approaching pickup.

With yet another August slipping away, consumed by the ever-present need to address mountains of vegetables before they rot, my mind started to think about the physics and especially the energy required to preserve the sunshine captured by my garden over the past four months. Although I have a 20-cubic-foot upright freezer, I’m proud to consider myself a canning guy. Let’s face it, anybody can fill a Ziploc and throw it in the freezer and not so much as break a sweat.

Canning requires absorbing decades of secret knowledge accumulated by the apron-wearing ancients as they toiled and perspired over enameled cast iron stoves fired by seasoned oak and hickory split and stacked two years prior. That, or spending about 15 minutes with the Ball Blue Book. Even so on the latter, canning requires determination, planning, and above all, grit, something the Aproned Ancients had in spades.

I do my canning outside on a two-burner propane cooker so as not to unnecessarily heat up the kitchen, which means heating up the whole house if the house is a two-bedroom cracker box. If you don’t know, canning requires a boiling water bath for acidic foods like tomatoes and any pickled thing, and a pressure cooker for non-acidic stuff like beans and corn. I have both and if you have an interest in getting started with this, I recommend first checking secondhand stores because they can be junkyards for this stuff, donated by the gritless descendants of the departed AAs.

Secondhand stores are also the Tomb of Tutankhamun of canning jars. I find the secondhand jar cost to be similar to new jars, but, and I can’t emphasize this enough, the old jars are so much better than new ones, it’s crazy to call them both ‘canning’ jars. It’s really a crapshoot when you load new jars into a pressure cooker; my experience is that about 10% won’t make it out unbroken. I figure those old jars have made it to high pressure (15 psi) Hell and back a few dozen times and they seemingly will last forever. These old jars were made with borosilicate glass, something too expensive for our disposable society; new jars are often made now with cheap soda lime glass. The thermal expansion properties of borosilicate glass are more than three times better than soda lime glass.

My favorites are the old Atlas (or Hazel Atlas) jars and I always buy them when I see them at the secondhand stores. I direct my confidantes to do the same for future reimbursement. They were made from 1902 until 1964 and their reputation endured far longer. Classico sold their spaghetti sauce in jars stamped Atlas Glass as an enticement and prior to 1989 they could be reused as home canning jars. I have a couple of these and use them for canning but they feel cheaper in your hand. Also excellent (but rare) are Drey jars (last one made in 1938), and Longlife (last one made in the 1960s). Old Ball brand jars are also quite durable and the good thing about old-time Ball jars is that a lot of them are pints. It’s pretty rare to find those other old brands in sizes anything other than quarts, and half gallons seem to be more numerous than pints. I suspect that reflects differences in preference ‘back then’ compared to the modern day. The new generic jars sold at stores like Walmart and Theisens are so bad the makers don’t even put their name on them.

It gives me the warmest of fuzzies to hold a century-old jar containing today’s sauce or pickles, and I let myself think that this karma is causing an AA to turn over in her grave with a smile on her face. But back to my earlier question about energy—do the energy costs pencil out compared to freezing?

There are 30 quarts in a cubic foot meaning my 20 cubic foot freezer could theoretically hold 600 quarts of food if every bit of available space was occupied—obviously an impossibility. Containers—even Ziploc bags—have volume and experience tells me that 80% of the listed capacity is probably best-case; therefore 480 quarts in my freezer. The manufacturer (Maytag) states it uses 525 kwh/year (1.8 million BTU) and to make things simple I’ll assume everything in there is stored for a year so that means 3750 BTU to store each quart of food.

Propane powers my two-burner cooker that I use for canning. A 20-lb tank of propane contains 430,000 BTU. I’m ballparking it from experience, but I think I can get around 20 batches of 7 quarts each (140 quarts) on a tank of propane, thus about 3,071 BTU to preserve a quart of food by canning. This is using the boiling water bath method which requires much more water (and therefore heating energy) than the pressure canner/cooker. An educated guess is that doing everything in the pressure cooker would reduce the required energy by at least half, i.e. about 1500 BTU per quart. Poking around on the internet seems to confirm the modest but not enormous amount of energy saved in canning versus freezing. That all being said, I’m using a fossil fuel (propane) to can my vegetables while at the same time, more than 50% of the electricity powered by my freezer is generated by renewable wind.

The up-front costs also must be considered. My freezer cost $900 and it obviously took some energy to construct and transport it. My two-burner cooker, boiling water canner, pressure cooker, jars, and propane tank were about a $400 investment in canning. I also must buy jar lids each year and I estimate that expense to be around $50. Freezing retains nutrients better; canned food is far easier to organize and give away to friends and family.

But there can be no doubt that canning is more work and much of it hot, whether you do it outside like me, or not. Anybody can learn how to do it in two shakes; even still, you feel a sense of accomplishment with canning that you don’t with freezing food. People know it takes some grit. And I sense in my bones that preserving food in this way is a cultural link to our agrarian past here in Iowa and it’s a reminder that like so many things about modern life, the reduction in labor that freezing provides comes at cost—energy and the purchase of an expensive appliance.

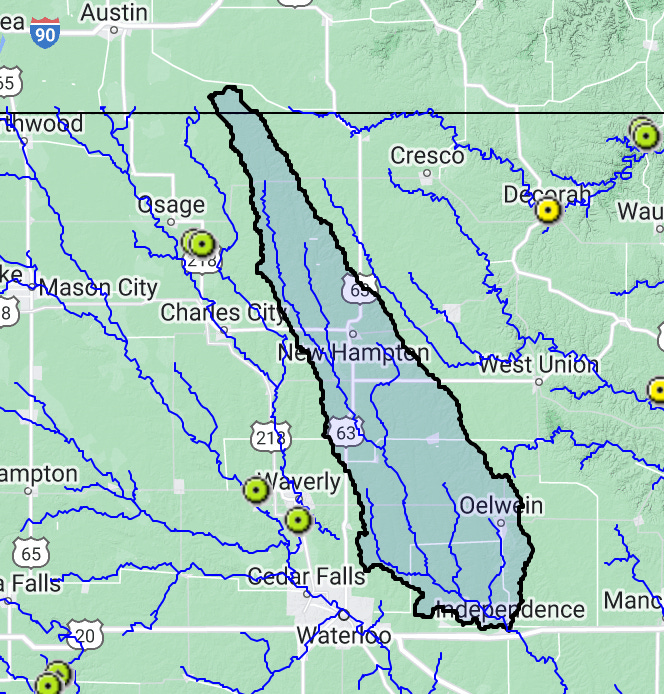

Quasqueton’s (Iowa) favorite son and smallmouth bass terrorist Orlan Love tells me his favorite river, the Wapsipinicon, is low. Very, very low. Only 20 cubic feet per second (CFS) of water recorded today (8/21) at the USGS gauge in Independence. Fun facts: that’s still 13 million gallons per day which sounds like a lot but is far less than what the city of Des Moines would require in a day for municipal supply. It equates to 20 gallons of water entering the river from each acre upstream of the gauge, on average of course. During drought, water is entering the river primarily from shallow alluvial (river valley) aquifers and whatever is being discharged by upstream municipal wastewater treatment plants. The lowest flow ever recorded for the date was 9 CFS in 1936. I’m going to write more about this later this week.

About my book: The Swine Republic is a collection of essays about the intersection of Iowa politics, agriculture and environment, and the struggle for truth about Iowa’s water quality. Longer chapters that examine ‘how we got here’ and ‘the path forward’ bookend the essays. Foreword was beautifully written by Tom Philpott, author of Perilous Bounty. Get a free copy of the book with an annual paid subscription to this substack ($30 value).

I, too, am guilty of erring on the side of "being sure to plant enough". After thorough analysis, I've determined that my problem all starts in the fall, when I scrupulously clean up all the beds. Therefore, in the spring, it's so easy to just pop the seeds and seedlings into the waiting earth. Only later, starting in July, does my folly become evident. One would think that after 70 years I would have wised up.

I enjoyed the canning jar tips; and the mathematical calculations --they help in efforts to legitimize our foolishness.

Ahhhh, canning. How do you keep the sweat bees away when you can outside. You prep inside and can outside? I'm embarrassed to admit I've caved and we installed an air conditioner! I LOVE to can indoors in the cool and it feels so decadent.

I'm truly impressed you've maintained the size of your garden. Mine has decreased in size by 75%!