Bureau Behaving Badly

Exhibit A On Why Putting Ag in Control of Water Quality Policy is a Bad Idea

This is a follow up from my last post that was intended to serve as primer for the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy and the supporting Iowa Nutrient Research Center. Knowledge of both of those things will help you understand what follows. ‘FB’ in the emails shown below are an abbreviation for Farm Bureau.

Researchers at the three Iowa Board of Regents institutions (Iowa State, University of Iowa, University of Northern Iowa) are invited every year to submit research proposals to the Iowa Nutrient Research Center (INRC). These proposals must focus on some aspect of Iowa’s nutrient pollution problem, and a list of priority topics are developed and disseminated prior to INRC issuing the Request for Proposals (RFP).

In 2017, a Northwest Iowa farmer approached us at the University of Iowa about doing a research project on land he farmed. I’m not going to reveal the farmer’s identity here (his name is blocked out in images of the emails that follow) because all indications are he was acting in good faith and through no fault of his own became somewhat of a target to other farmers around him. This particular farmer had seen the Iowa Water Quality Information System (WQIS) that posted water quality sensor data in real time and was intrigued with the tool, and visited the website with some frequency. His vision was that he would adopt practices on a field while sensors measured water quality in a stream flowing through the property.

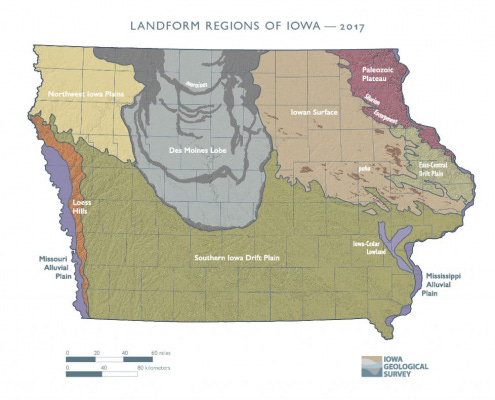

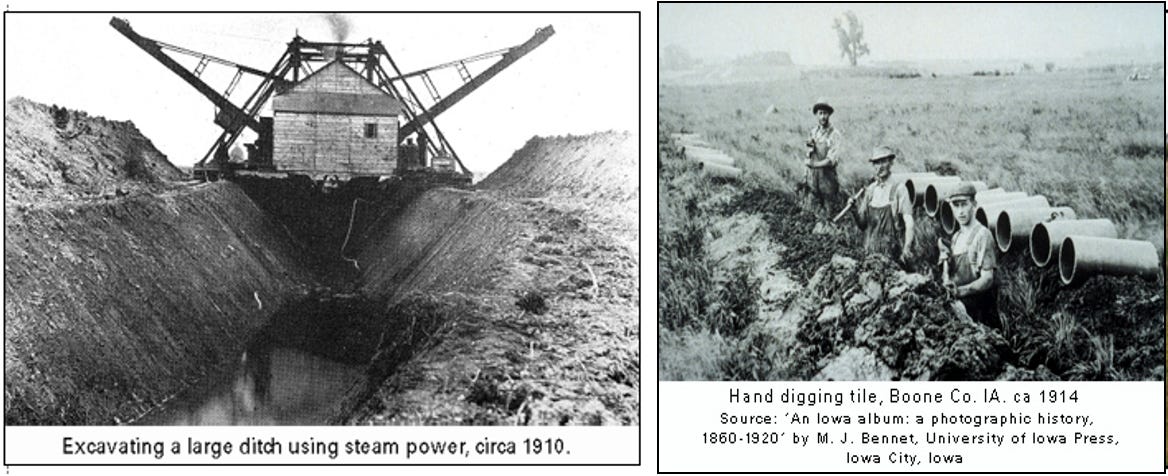

That stream was Hardin Creek, a tributary to the Raccoon River. Hardin Creek is like many north central Iowa streams in that it is much longer now than prior to European settlement. The upper reaches of these watersheds were once densely-packed with pothole wetlands. As agricultural drainage tile was installed in the pre-1910 era to lower the water table and drain the wetlands, it was necessary to create outlets for the water. Streams like Hardin Creek were extended upward into the watershed as trapezoidal ditches formed by steam shovels. Thus you see many of them as meandering streams in their lower reaches but straight ditches in the upper reaches.

Water in these upper reaches often has mind-bogglingly high nutrient concentrations; 100 ppm nitrate, 10 times the drinking water standard, is not out of the question for some of them in some years. That being said, they do serve as habitat for wildlife and recreation for some people. Farmers constantly are at war with beavers that see them as the easiest of pickings when it comes to dam building.

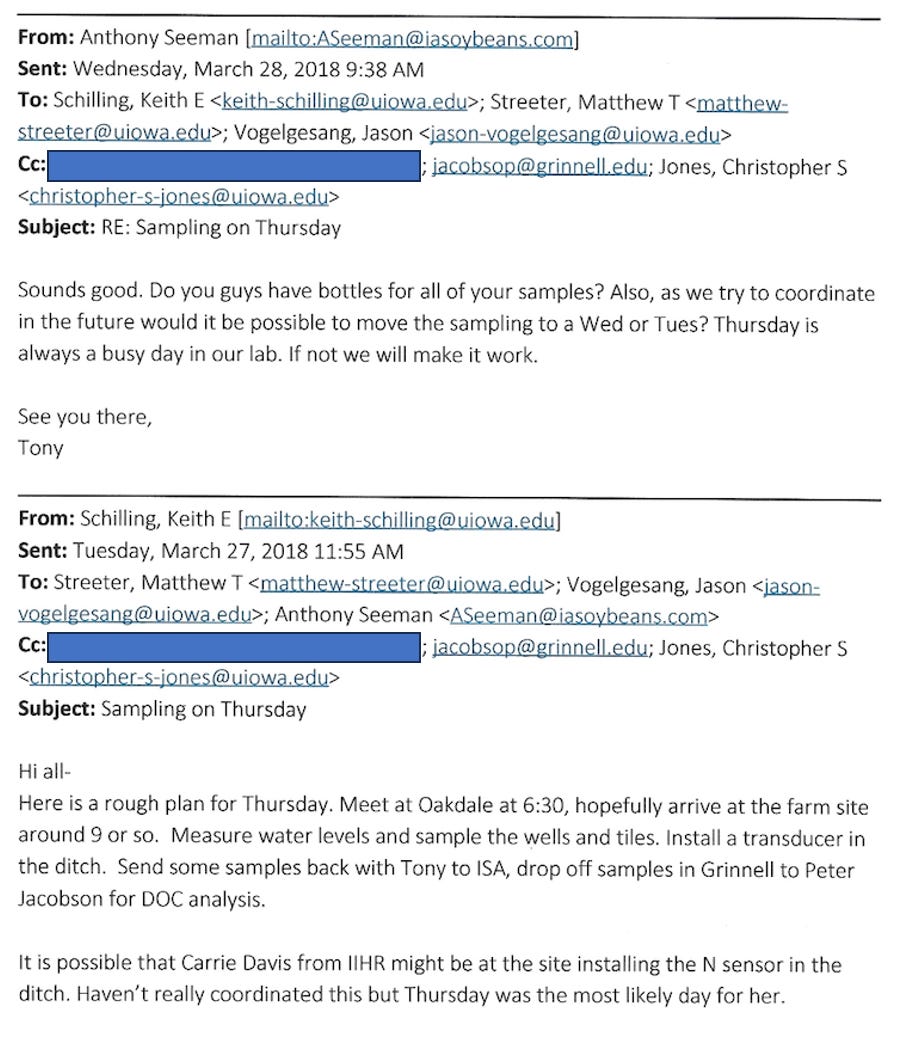

The Iowa Geological Survey (part of the University of Iowa) developed a research proposal around the farmer’s vision that included not only monitoring of the stream with sensors but also shallow groundwater in the field itself at multiple locations. The lead (principle) investigator was Dr. Keith Schilling of IGS with several partners including myself as the supervisor of UI’s water quality sensor network. Faculty at Grinnell College was also part of the proposal, this to conduct some lab analysis of water samples from the project. Iowa Soybean Association was also an institutional partner.

The proposal was independently reviewed and chosen to be funded by the INRC (housed at ISU, I might emphasize) along with others in FY 2018. There was little about the project that seemed controversial to us, although by that time it was well known that some in agriculture and the legislature disliked the water quality sensor network and WQIS.

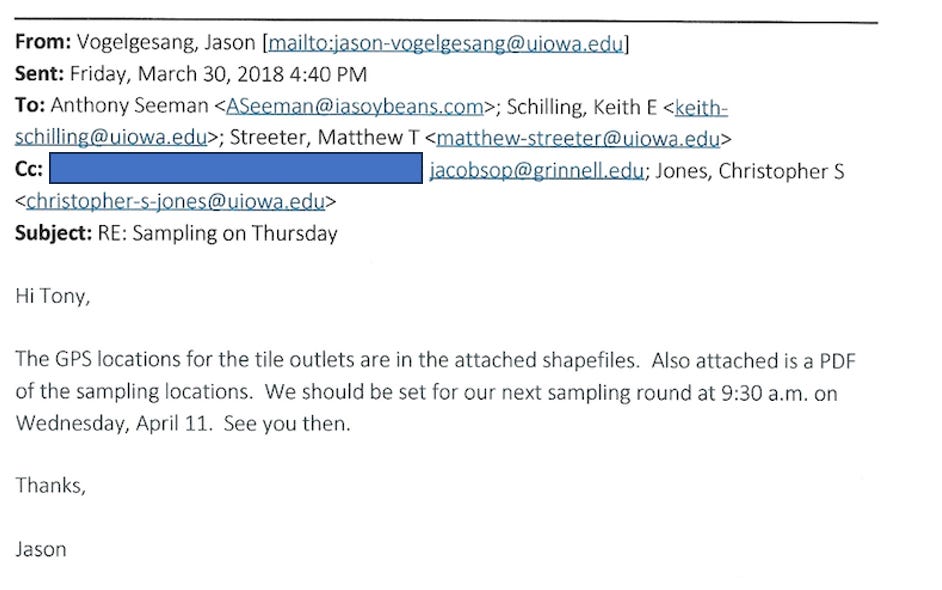

Early tasks in the project included ‘grab’ samples to be submitted for lab analysis, as mundanely described in the emails above. Drainage tile outlets from the field to Hardin Creek were mapped and sampled, as described in the email below.

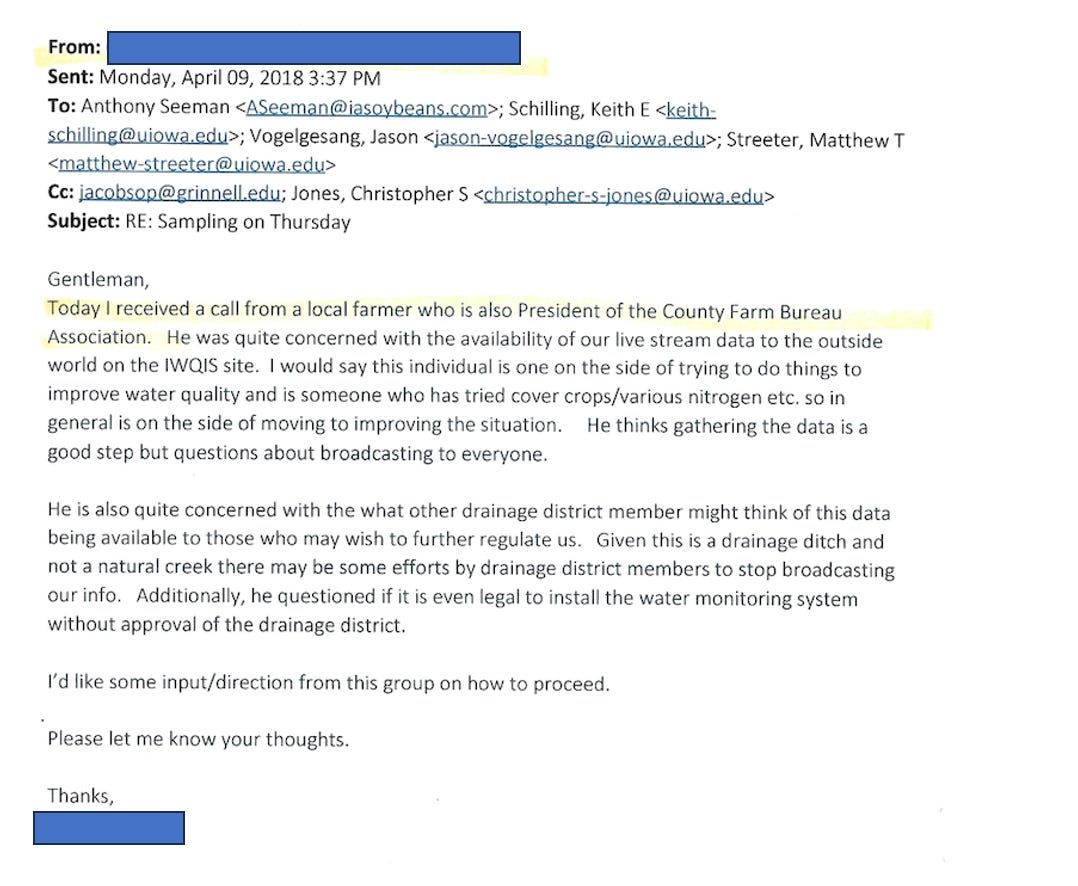

Things got interesting as UI began deploying the water quality sensors in Hardin Creek the first week of April (2018). Field staff reported back that area farmers stood by watching menacingly as equipment was deployed in the creek. Then this email was received from the farmer on April 9:

A couple of things about the above email. Whether or not the stream is ‘natural’ is not germane to the discussion, an issue that also comes up later. Hardin Creek at this site is a perennial stream and would be considered a ‘Water of the U.S.’ This is the type of stream that was expressly exempted from regulation from the now infamous WOTUS controversy at the center of the recent U.S. Supreme Court decision. The public did and does have access to the stream at road crossings and evidence of past angling was near the project site. The stream would be easily navigable by canoe or kayak at the project site some days and months during the year.

Concerning the mention of 'drainage district’: there are about 3000 of these in Iowa and they are defined in Iowa Code. They have responsibility for oversight, maintenance and expansion of constructed drainage throughout Iowa. A person can think of a drainage district as a watershed, or, as we say when conducting research on these systems, a tileshed. There can be many drainage districts within one county, and in many cases the elected county supervisors also oversee the drainage district. Drainage districts in Iowa have taxing authority over the property owners whose field drainage ties into the drainage district infrastructure.

Also curious is the farmer’s comment that the data might be used to ‘further regulate us.’ The reader here should know that there is virtually no regulation of tile drainage or drainage district water in Iowa and there are no nutrient standards (i.e. nitrate and phosphorus) for stream or tile water. In fact, exemption of tile water from regulation was central to the failure of Des Moines Water Works lawsuit that targeted three counties (and their drainage districts) lying upstream of Des Moines in the Raccoon River watershed.

Clear from the above email is that farmers in the area feared what sort of nitrate concentrations might be present in the stream.

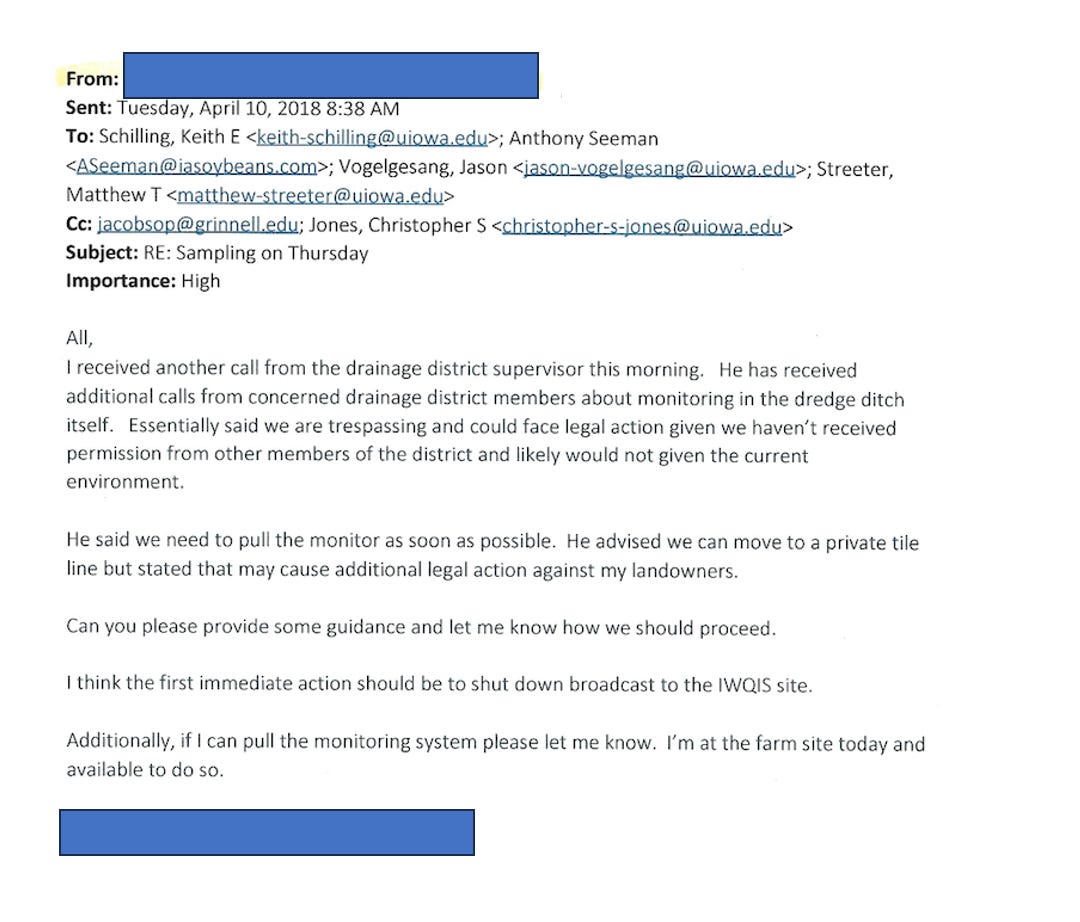

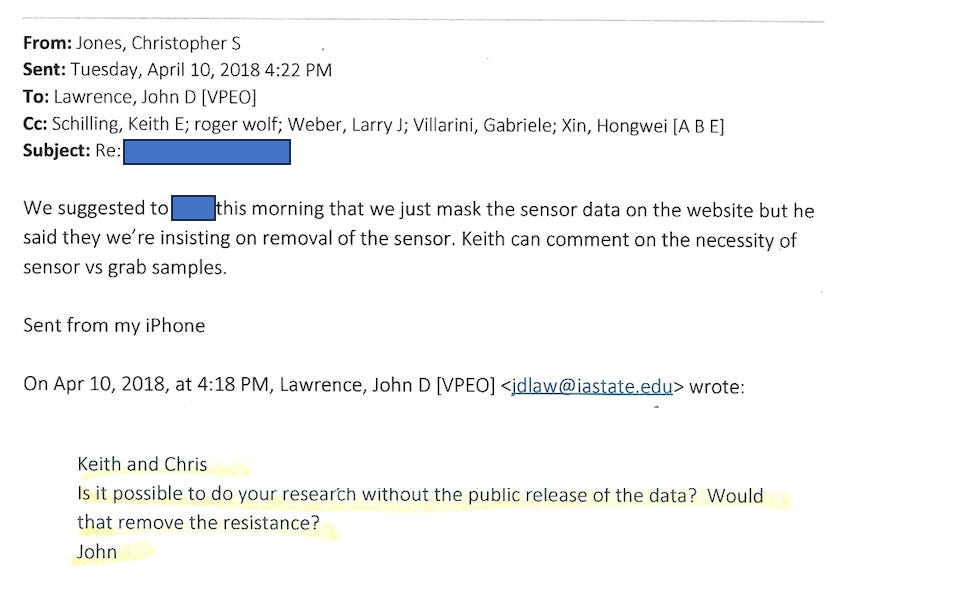

The farmer sent the following email the next day (4/10/2018):

You can see from the above email that the rest of the drainage district was asserting monitoring the ditch to be a trespass. At the time we felt this was absurd and I still feel this way; regardless, we had the farmer’s permission to cross the property and access Hardin Creek which was clearly a perennial stream being used by the public and one that has/had a continuous connection to the North Raccoon River in most years. Iowa Soybean Association had been conducting water monitoring on the stream since about 1999 and one tributary of Hardin Creek had been monitored in the past by Iowa DNR. Nonetheless, this is the card the farmers in the drainage district chose to play. As of this day (4/10) we all had been quickly arriving at the idea that the data from the sensors would be masked from public view on WQIS in the hopes calmer heads would prevail and let the sensors themselves remain for the benefit of the project.

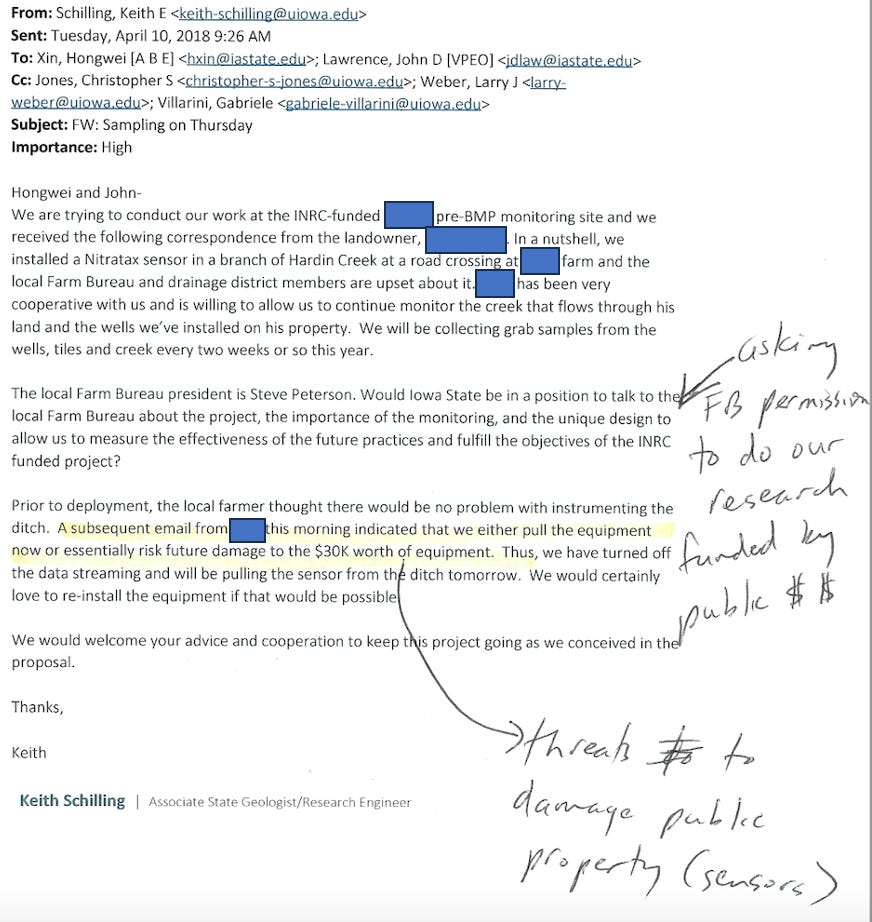

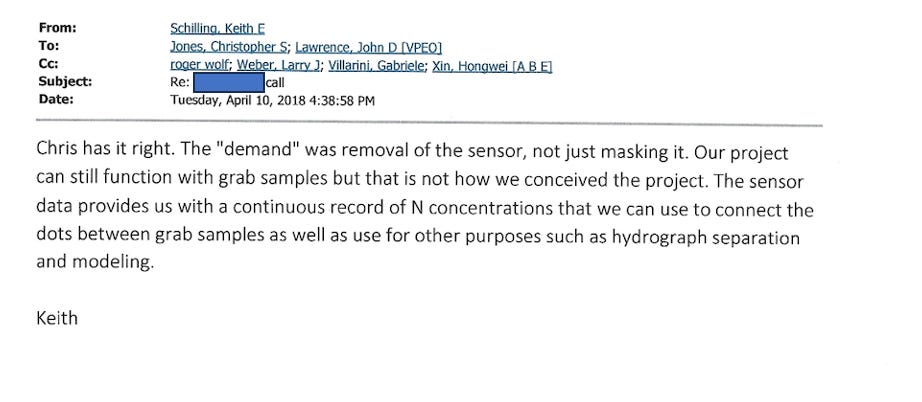

Later in the day Keith Schilling sent the email shown below. Hand written notes on the paper were made by me shortly after the episodes described in this post. I had started saving and printing the emails with idea that some day I might talk publicly about this.

You can see the email is intended to inform Hongwei Xin (Professor at ISU and Director of the INRC at the time) and John Lawrence (VP of Extension and Outreach at ISU, now retired) of the situation at the farm and creek. You can see Dr. Schilling is essentially asking Iowa State to intervene for us and ask Farm Bureau permission to allow us to continue research on this publicly-funded project. The farmer had called me either that morning (or perhaps the previous day) and I summarized my conversation with him in the email below.

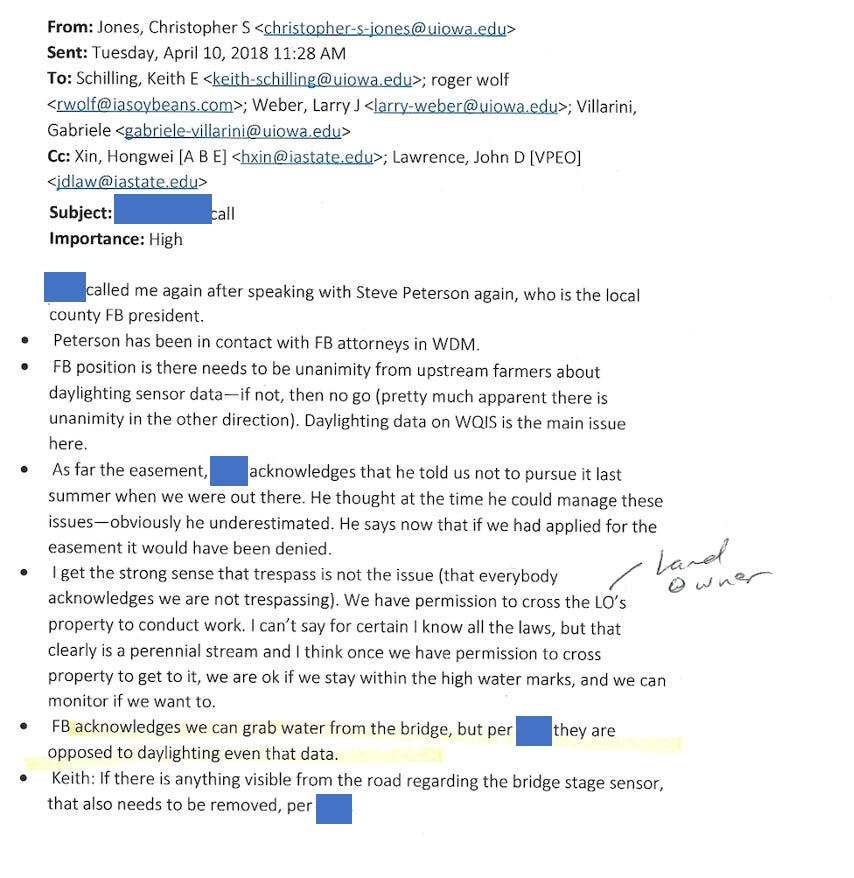

You can see that the farmer gave me the impression that, despite drainage district comments to the contrary, trespass was not the issue. Rather it was collection of water quality data and daylighting the data on WQIS. The discussion of a road easement is common when deploying water quality sensors, which are often situated in the right-of-way (ROW). I cannot recall with certainty if one of the sensors for this project was in the ROW, but I think one was (there were two in total for the project). The farmer had assured us the previous fall that we would not need an easement so we did not pursue one. In retrospect, I think the farmer probably knew an easement application by UI would raise some red flags and thus advised us not to apply for one. It was probably a mistake on my part to go along with the farmer’s wishes at the time.

The following are three responses to my email above.

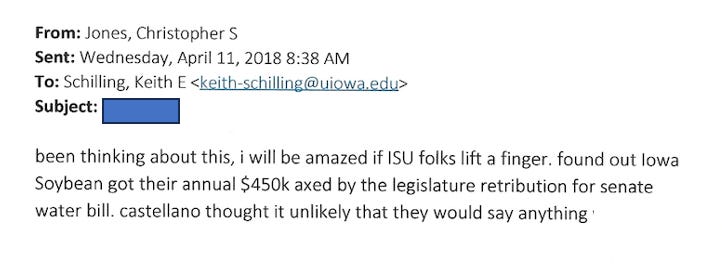

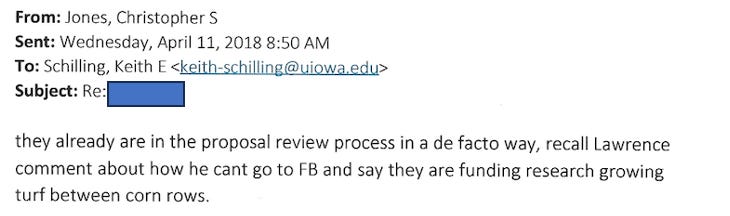

So we can see from highlighted text above that we have an Iowa State Vice President (Lawrence) asking us if we can do publicly-funded research without making the publicly-funded data collection available to the public. The following is an email exchange between Keith Schilling and me the next morning.

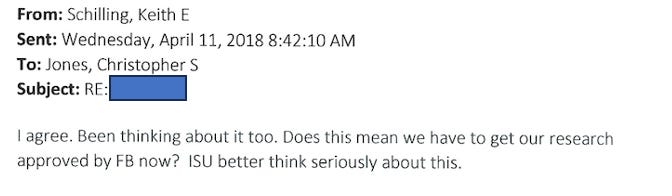

The first (top) email refers to a conversation I had with Mike Castellano who was and is a professor in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS) at Iowa State. The second email is Keith contemplating the now very plausible idea that INRC-funded research needed Farm Bureau sign-off before it was funded. The last (bottom) email refers to a previous conference call led by John Lawrence concerning priority research objectives for INRC. Turf grown between corn rows is a credible research topic and a potential best management practice (BMP) for reducing nitrate loss from corn fields. Dr. Lawrence made the comment that Farm Bureau would not take this idea seriously and in doing so, implied that Farm Bureau was part of the proposal review and/or approval process.

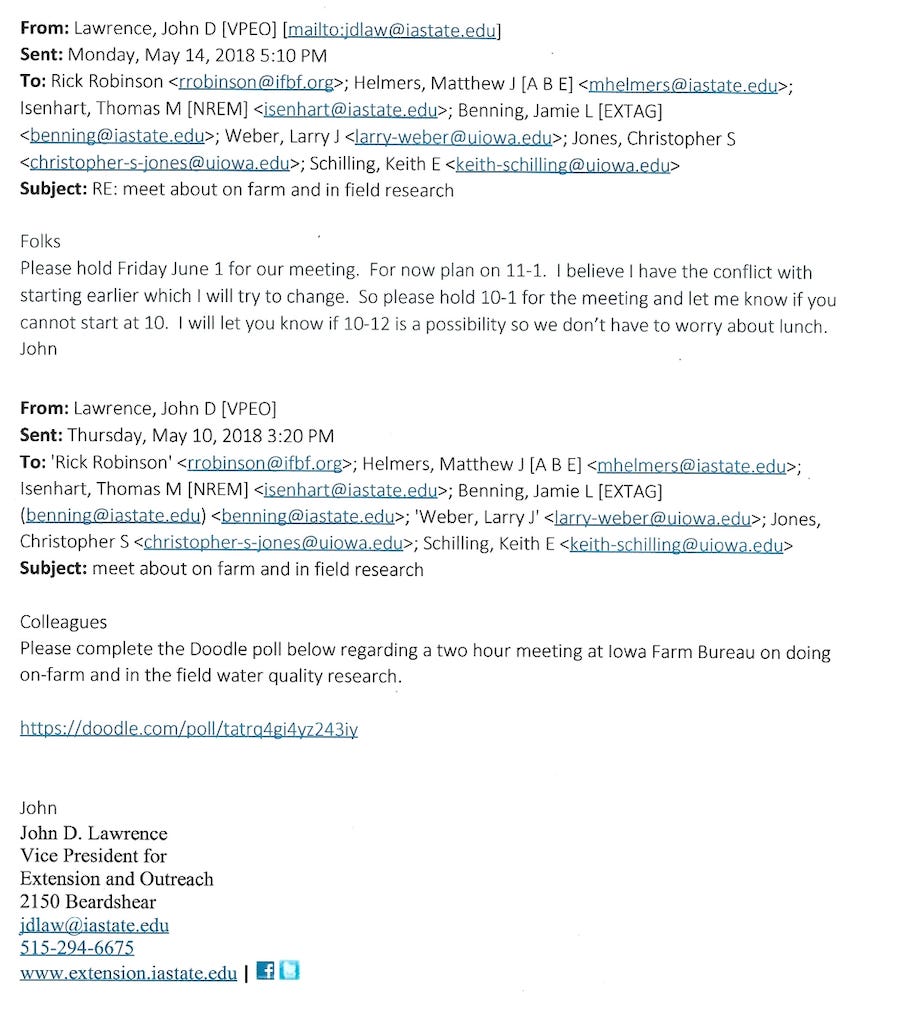

I don’t recall very clearly project related events between 4/11/18 and 5/10/18, but at some point in that time window discussion(s) took place about hashing out the issues with Farm Bureau. Dr. Lawrence took the lead in arranging this.

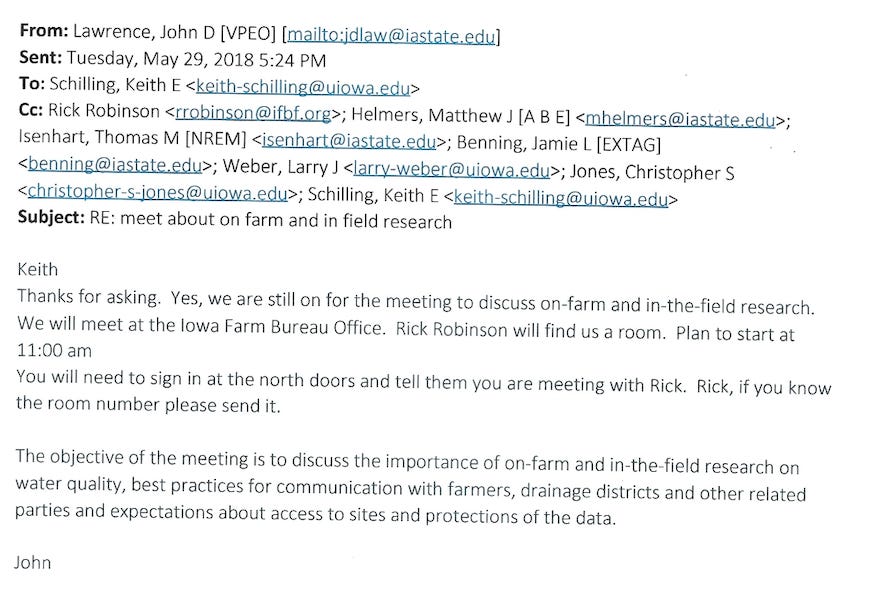

The meeting was held June 1, 2018 at Farm Bureau headquarters in West Des Moines. The attendees were Schilling, Larry Weber and me from the University of Iowa/Iowa Geological Survey; Tom Isenhart, Matt Helmers and Lawrence from Iowa State; Farm Bureau Environmental Policy Director Rick Robinson; Farm Bureau Government Relations Counsel Christina Gruenhagen, and one other person from Farm Bureau who I took at the time to be an intern but I can’t be certain of that. Isenhart and Helmers were both ISU faculty at the time; Helmers is now the director of INRC. Larry Weber was and is director of IIHR-Hydroscience & Engineering at UI and was my boss during most of my time at UI. Robinson, Lawrence and me are all retired.

Despite Lawrence’s rather innocent-sounding meeting objective, it was clear, to me anyway, the objective of the meeting was for Farm Bureau to intimidate us into not ever again trying anything so crazy as to use water quality sensors and WQIS to broadcast data from INRC-funded on-farm research projects. I did not take notes at the meeting but I also recall discussion of our (UI) recently published paper showing nitrate levels increasing in Iowa streams going back to 2003. I recall Gruenhagen commenting in an unfavorable way that the paper gave ammunition to those advocating for regulation of environmental outcomes in Iowa—as if that was something we as researchers should avoid. Farm Bureau staff repeatedly made the assertion that we needed express permission from each and every landowner upstream of the project site to conduct monitoring, obviously an impossible task.

Long and short, as a group we did not challenge the Farm Bureau demands and left with the matter settled: sensors would not be used at the project. If you’re wondering about the hierarchy of the six university people, Keith and I were the only ones that were not tenured faculty and thus were at the bottom, despite being closest to the project. It was well known that Lawrence had an ongoing relationship with Farm Bureau staff (he also was/is a farmer) and I think it’s fair to say we all followed his lead. I’m convinced if the six of us went into the meeting unified and defiant, things might look a little differently today as they relate to the both the Nutrient Strategy and the Nutrient Research Center. Was it worth it at time to take that risk? I thought so, but admittedly I was no more courageous than the rest of the group at the time.

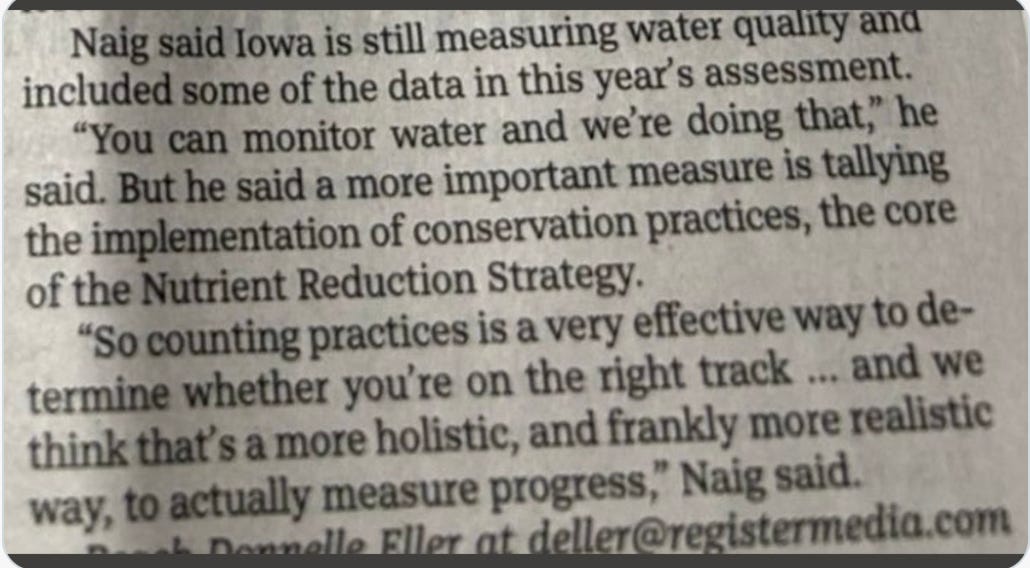

I’m telling this story now because I think it informs current events surrounding Iowa water quality and the nutrient strategy. For example, people close to the strategy, such as secretary of agriculture Mike Naig, have openly dismissed the relevance of water quality monitoring to the nutrient strategy. We’ve also seen the 2023 legislature try to completely defund the water quality sensor network. It’s clear to anybody that wants to look that the actual quality of the water and research conducted to examine it is not what’s important here—it’s the public’s perception of agribusiness and the Iowa farmer within the context of the state’s degraded water.

I would also ask the question—why is an insurance company (Farm Bureau) allowed to get anywhere near the process of funding and conducting research at a public institution? How can this be healthy for the 98% of us that don’t farm?

People and institutions that try to suppress information about the condition of Iowa water cannot and must not be considered to be good faith partners while the rest of us try to tackle the colossal problem that is Iowa’s polluted water. What they say about these topics should not be taken seriously. It was at this meeting at Farm Bureau headquarters where this idea became crystallized in my mind, and on that day I decided to start writing in a forthright way about the issue.

And finally, why have agricultural interests been assigned an authoritative role in mitigating the pollution and environmental degradation the industry itself created? This is perverse policy, and being that I am always in search of a good metaphor, will say this is tantamount to Vladimir Putin being assigned with the rebuilding of Ukraine while continuing to allow him to bomb orphanages and hospitals.

Iowa’s rivers, lakes, aquifers and natural systems have been wrecked by the corn/soy/CAFO production system. Inviting the major players of that system to take charge of the supposed restoration is an idea born in Hell.

I am a crop advisor in western NY. I write CAFO plans and am also a TSP for NRCS. I've listened to your podcast a few times and find you to be quite reasonable. Sad to say, I am not surprised by anything you wrote.

The thing I have come to realize in the last number of years is that all of our regulatory agencies in all industries: agrichemical, Pharma, medical, industry, etc. are basically subject to the same cronyism and influence as the industry I am most familiar with. Unfortunately, it is a question of ethics and our country seems to have lost any ethical sense that it may have once had.

Agree completely regarding the Farm Bureau!

Increasingly, corporate funded research and research parks are becoming primary methods of garnering funding for ag (and other) research at public universities. I don't see many un-tenured professors that are going to risk doing research 'for the public good' when the funding of their very institution is so dependent on private industrial funding. Even tenured professors put the funding of their entire university at risk by conducting environmental research that shines any kind of negative light on industrial agriculture. Public universities as citadels of free-thinking and innovation? Not so much. . .